|

"Spengler" takes the pseudonym he writes under from Oswald Spengler (1880-1936), the famous author of The Decline of the West. He has been writing online commentaries for Asia Times Online since 2000.

Admit It — You Really Hate Modern Art

By Spengler

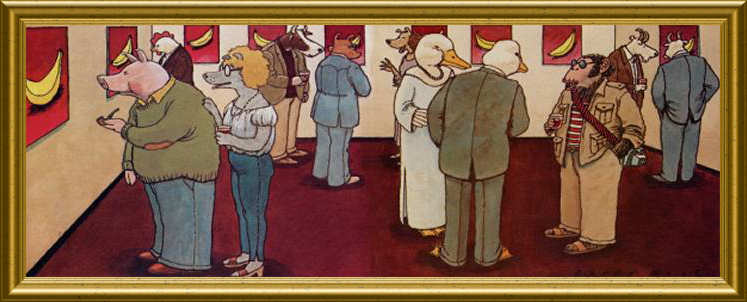

There are esthetes who appreciate the cross-eyed cartoons of Pablo Picasso, the random dribbles of Jackson Pollock, and even the pickled pigs of Damien Hirst. Some of my best friends are modern artists. You, however, hate and detest the 20th century's entire output in the plastic arts, as do I.

"I don't know much about art," you aver, "but I know what I like." Actually you don't. You have been browbeaten into feigning pleasure at the sight of so-called art that actually makes your skin crawl, and you are afraid to admit it for fear of seeming dull. This has gone on for so long that you have forgotten your own mind. Do not fear: in a few minutes' reading I can break the spell and liberate you from this unseemly condition.

First of all, understand that you are not alone. Museums are bulging with visitors who come to view works they secretly detest, and prices paid for modern art keep rising. One of Jackson Pollock's drip paintings sold last year for US$140 million, a striking result for a drunk who never learned to draw, and splattered paint at random on the canvas.

Somewhat more modest are the prices paid for the grandfather of abstract art, Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), whose top sale price was above $40 million. An undistinguished early Kandinsky such as 'Weilheim-Marienplatz' (43 by 33 centimeters) will sell for $4 million or so by Sotheby's estimate. Kandinsky is a benchmark for your unrehearsed response to abstract art, for two reasons. First, he helped invent it, and second, he understood that non-figurative art was one facet of an esthetic movement that also included atonal music. Kandinsky was the friend and collaborator of the grandfather of abstract music, composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), who also painted. Schoenberg, like Kandinsky, is universally recognized as one of the founders of modernism.

Kandinsky attended a performance of Schoenberg's music in 1911, and afterward wrote to Schoenberg:

Please excuse me for simply writing to you without having the pleasure of knowing you personally. I have just heard your concert here and it has given me real pleasure. You do not know me, of course—that is, my works—since I do not exhibit much in general, and have exhibited in Vienna only briefly once and that was years ago (at the Secession). However, what we are striving for and our whole manner of thought and feeling have so much in common that I feel completely justified in expressing my empathy. In your works, you have realized what I, albeit in uncertain form, have so greatly longed for in music.

Kandinsky was entirely correct in his judgment. An enormous literature exists on the relationship between abstract painting and atonal music, and the extensive Kandinsky-Schoenberg correspondence can be found on the Internet. For those who like that sort of thing, as Abraham Lincoln once said, it is just the sort of thing they would like.

The most striking difference between the two founding fathers of modernism is this: the price of Kandinsky's smallest work probably exceeds the aggregate royalties paid for the performances of Schoenberg's music. Out of a sense of obligation, musicians perform Schoenberg from time to time, but always in the middle and never at the end of a program, for audiences flee the cacophony. Schoenberg died a poor man in 1951, and and his widow and three children barely survived on the copyright royalties from his music. His family remains poor, while the heirs of famous artists have become fabulously wealthy.

Modern art is ideological, as its proponents are the first to admit. It was the ideologues, namely the critics, who made the reputation of the abstract impressionists, most famously Clement Greenberg's sponsorship of Jackson Pollock in The Partisan Review. It is not supposed to "please" the senses on first glance, after the manner of a Raphael or an Ingres, but to challenge the viewer to think and consider.

Why is it that the audience for modern art is quite happy to take in the ideological message of modernism while strolling through an art gallery, but loath to hear the same message in the concert hall? It is rather like communism, which once was fashionable among Western intellectuals. They were happy to admire communism from a distance, but reluctant to live under communism.

When you view an abstract expressionist canvas, time is in your control. You may spend as much or as little time as you like, click your tongue, attempt to say something sensible and, if you are sufficiently pretentious, quote something from the Wikipedia write-up on the artist that you consulted before arriving at the gallery. When you listen to atonal music, for example Schoenberg, you are stuck in your seat for a quarter of an hour that feels like many hours in a dentist's chair. You cannot escape. You do not admire the abstraction from a distance. You are actually living inside it. You are in the position of the fashionably left-wing intellectual of the 1930s who made the mistake of actually moving to Moscow, rather than admiring it at a safe distance.

That is why at least some modern artists come into very serious money, but not a single one of the abstract composers can earn a living from his music. Non-abstract composers, to be sure, can become quite wealthy, for example Baron Andrew Lloyd Webber and a number of film composers. American Aaron Copland (1900-90), who mainly wrote cheerful works filled with local color (e.g., the ballets 'Billy the Kid' and 'Appalachian Spring'), earned enough to endow scholarships for music students. Viennese atonal composer Alban Berg (1885-1935) had a European hit in his 1925 opera 'Wozzeck', something of a compromise between Schoenberg's abstract style and conventional Romanticism. His biographers report that the opera gave him a "comfortable living."

After decades of philanthropic support for abstract (that is, atonal) music, symphony orchestras have given up inflicting it on reluctant audiences, and instead are commissioning works from composers who write in a more accessible style. According to a recent report in the Wall Street Journal, the shift back to tonal music "comes as large orchestras face declining attendance and an elderly base of subscribers. Nationwide symphony attendance fell 13% to 27.7 million in the 2003-04 season from 1999-2000, according to the American Symphony Orchestra League."

The ideological message is the same, yet the galleries are full, while the concert halls are empty. That is because you can keep it at a safe distance when it hangs on the wall, but you can't escape it when it crawls into your ears. In other words, your spontaneous, visceral hatred of atonal music reflects your true, healthy, normal reaction to abstract art. It is simply the case that you are able to suppress this reaction at the picture gallery.

There are, of course, people who truly appreciate abstract art. You aren't one of them; you are a decent, sensible sort of person without a chip on your shoulder against the world. The famous collector Charles Saatchi, proprietor of an advertising firm, is an example of the few genuine admirers of this movement. When Damien Hirst arranged his first student exhibition at the London Docklands, reports Wikipedia, "Saatchi arrived at the second show in a green Rolls-Royce and stood open-mouthed with astonishment in front of (and then bought) Hirst's first major 'animal' installation, 'A Thousand Years', consisting of a large glass case containing maggots and flies feeding off a rotting cow's head."

The Lord of the Flies is an appropriate benchmark for the movement. Thomas Mann in his novel Doktor Faustus tells the story of a composer based mainly on Arnold Schoenberg, whom resentment drives to make a pact with the Devil. Mann's protagonist cannot create, so out of rancor sets out to "take back" the works of Ludwig van Beethoven, by writing atonal lampoons of them that will destroy the listener's ability to hear the original.

Many critics maintain that Picasso's famous painting originally named 'The Bordello at Avignon' (Les Demoiselles d'Avignon) was the single most influential modernist statement. In this painting Picasso lampooned El Greco's great work 'The Vision of St John'. Picasso reduces the horror of the opening of the Fifth Seal in the Book of Revelation to a display of female flesh in a whorehouse. Picasso is trying to "take back" El Greco, by corrupting our capacity to see the original.

By inflicting sufficient ugliness upon us, the modern artists believe, they will wear down our capacity to see beauty. That, I think, is the point of putting dead animals into glass cases, or tanks of formaldehyde. But I am open-minded; there might be some value to this artistic technique after all. If Damien Hirst were to undertake a self-portrait in formaldehyde, I would be the first to subscribe to a commission.

* * * * * *

Why You Pretend to Like Modern Art

By Spengler

After I wrote 'Admit It — You Really Hate Modern Art', many readers assured me that I was quite mistaken about them. Especially among the educated elites there are many who will go to their graves proclaiming their love for modern art, and I owe them an explanation of sorts. At the cost of most of a few remaining friends, I will provide it.

You pretend to like modern art because you want to be creative. In fact, you are not creative, not in the least. In all of human history we know of only a few hundred truly creative men and women. It saddens me to break the news, but you aren't one of them. By insisting that you are not creative, you think I am saying that you are not important. I do not mean that, but will have to return to the topic later.

You have your heart set on being creative because you want to worship yourself, your children, or some pretentious impostor, rather than the God of the Bible. Absence of faith has not made you more rational. On the contrary, it has made you ridiculous in your adoration of clownish little deities, of whom the silliest is yourself. G. K. Chesterton said that if you stop believing in God, you will believe in anything.

For quite some time, conservative critics have attacked the conceit that every nursery-school child should be expected to be creative. Professor Allan Bloom observed twenty years ago in The Closing of the American Mind that creativity until quite recently referred to an attribute of God, not of humans. To demand the attribute of creativity for every human being is the same as saying that everyone should be a little god.

But what should we mean by creativity? In science and mathematics, it should refer to discoveries that truly are singular, that is, could not possibly be derived from any preceding knowledge.

We might ask: In the whole history of the arts and sciences, how many contributors truly are indispensable, such that history could not have been the same without their contribution? There is room for argument, but it is hard to come up with more than a few dozen names. Europe had not progressed much beyond Archimedes of Syracuse in mathematics until Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz invented the calculus. Until Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler, Europe relied on the 1st-century work of Ptolemy. After Kepler only Newton, and after Newton only Albert Einstein fundamentally changed our views on planetary motion. Scholars still argue over whether someone else would have discovered Special Relativity if Einstein had not, but seem to agree that General Relativity had no clear precedent.

How many composers, for that matter, created Western classical music? If only a dozen names are known to future generations, they still will know what is fundamental to this art form.1

We can argue about the origin of scientific or artistic genius, but we must agree that it is extremely rare. Of the hundreds of composers employed as court or ecclesiastical musicians during Johann Sebastian Bach's lifetime, we hear the work of only a handful today. Eighteenth-century musicians did not strive for genius, but for solid craftsmanship; how it came to be that a Bach would emerge from this milieu has no consensus explanation. As for the rest, we can say with certainty that if a Georg Phillip Telemann (a more successful contemporary of Bach) had not lived, someone else could have done his job without great loss to the art form.

If we use the term "creative" to mean more or less the same thing as "irreplaceable", then the number of truly creative individuals appears very small indeed. It is very unlikely that you are one of them. If you work hard at your discipline, you are very fortunate to be able to follow what the best people in the field are doing, and if you are extremely good, you might have the privilege of elaborating on points made by greater minds. Beneficial as such efforts might be, it is very unlikely that if you did not do this, no one else would have done it. On the contrary, if you are at the cutting edge of research in any field, you take every possible measure to publish your work as soon as possible, so that you may get credit for it before someone else comes up with precisely the same thing. Even the very best minds in a field live in terror that they will be made dispensable by others who circulate their conclusions first.

Bach inscribed each of his works with the motto, "Glory belongs only to God," and insisted (wrongly) that anyone who worked as hard as he did could have achieved results just as good. He was content to be a diligent craftsman in the service of God, and did not seek to be a genius; he simply was one. That is the starting point of the man of faith. One does not set out to be a genius, but rather to be of service; extraordinary gifts are a responsibility to be borne with humility. The search for genius began when the service of God no longer interested the artists and scientists.

Friedrich Nietzsche announced the death of God, and the arrival of the artist as hero, taking as his model Richard Wagner, about whose artistic merits we can argue on a different equation. Whether Wagner was a genius is debatable, but it is beyond doubt that the devotees of Nietzsche were no Wagners, let alone Bachs. To be free of convention was to create one's own artistic world, in Nietzsche's vision, but very few artists are capable of creating their own artistic world. That puts everyone else in an unpleasant position.

To accommodate the ambitions of the artists, the 20th century turned the invention of artistic worlds into a mass-manufacturing business. In place of the humble craftsmanship of Bach's world, the artistic world split into movements. To be taken seriously during the 20th century, artists had to invent their own style and their own language. Critics heaped contempt on artists who simply reproduced the sort of products that had characterized the past, and praised the founders of schools: Impressionism, Cubism, Primitivism, Abstract Expressionism, and so forth.

Without drawing on the patronage of the wealthy, modern art could not have succeeded; each day we read of new record prices for 20th century paintings, for example the estimated US$140 million paid to media mogul David Geffen for a Jackson Pollock. Very rich people like to flatter themselves that they are geniuses, and that their skill or luck at marketing music or computer code qualifies them as arbiters of taste. Successful business people typically are extremely clever, but they tend to be idiot savants, with sharp insight into some detail of industry that produces great wealth, but no concept whatever of issues outside their immediate field of expertise. Because the world conspires to flatter the wealthy, rich people are more prone to think of themselves as little gods than ordinary people, and far more susceptible to the cult of creativity in art.

In his great novel Doktor Faustus, Thomas Mann portrayed this as the work of the devil. The new Faust who makes a pact with Satan in this novel represents the composer Arnold Schoenberg, who sells his soul in return for a system for composing music.

A new class of critics served as midwives at the birth of these monsters. I marveled in the essay noted above over the fact that museum-goers gush over Pollock's random dribbles, but never would listen to Arnold Schoenberg's 12-tone compositions at a concert hall. The conductor Sir Thomas Beecham famously said that people don't like music; they only like the way it sounds. In the case of Pollock, people neither like his work nor the way it looks; what they like is the idea that the artist in his arrogance can redefine the world on his own terms.

To be an important person in this perverse scheme means to shake one's fist at God and define one's own little world, however dull, tawdry and pathetic it might be. To lack creativity is to despair. Hence the attraction of the myriad ideological movements in art that gives the despairing artists the illusion of creativity. If God is the Creator, then imitation of God is emulation of creation. But that is not quite true, for the Judeo-Christian God is more than a creator; God is a creator who loves his creatures.

In the world of faith there is quite a different way to be indispensable, and that is through acts of kindness and service. A mother is indispensable to her child, as are husbands, wives and friends to each other. If one dispenses with the ambition to remake the world according one's whim, and accepts rather that the world is God's creation, then imitatio Dei consists of acts of love.

In their urge toward self-worship, the artists of the 20th century descended to extreme levels of artlessness to persuade themselves that they were in fact creative. In their compulsion to worship themselves in the absence of God, they produced ideas far more ridiculous, and certainly a great deal uglier, than revealed religion in all its weaknesses ever contrived. The modern cult of individual self-expression is a poor substitute for the religion it strove to replace, and the delusion of personal creativity an even worse substitute for redemption.

Note

1. Josquin des Prez, Claudio Monteverdi, Bach, Domenico Scarlatti, George Frideric Haendel, Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Frederic Chopin, Johannes Brahms.

|