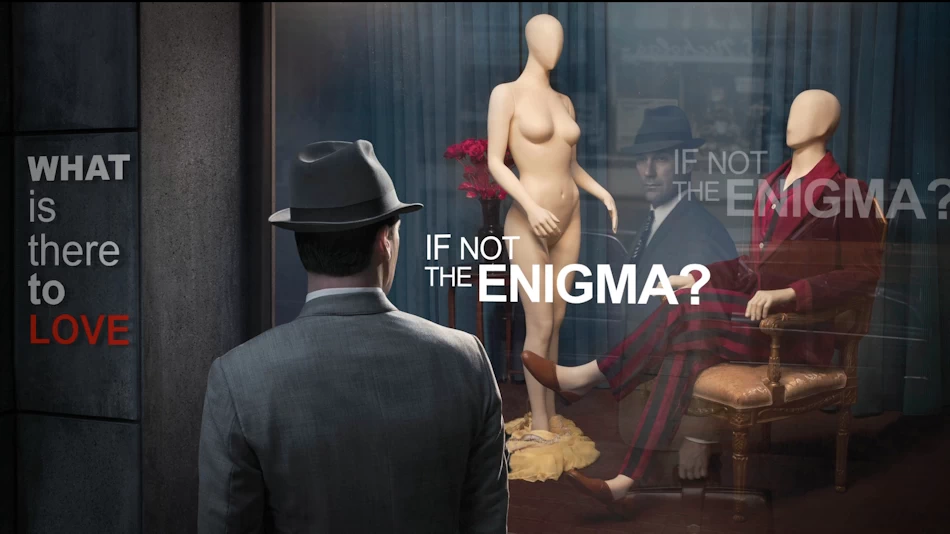

What Is There To Love If Not the Enigma?

Mad Men television series poster, season 5, 2012

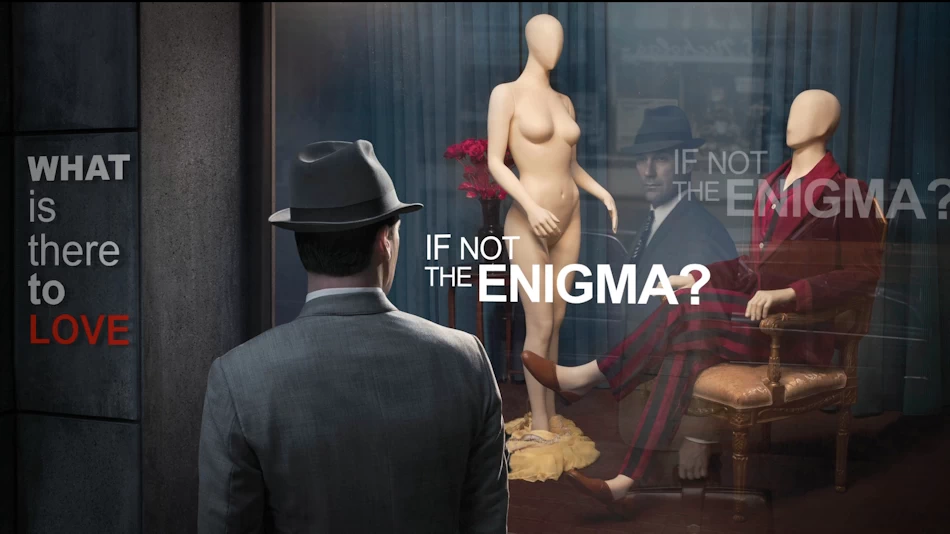

What Is There To Love If Not the Enigma?

Mad Men television series poster, season 5, 2012

Text transcribed from the 17-minute video on the blu-ray disc of Mad Men, Season 5, Disc 2 extra features, edited slightly for grammar and clarity.

The two speakers are:

Emily Braun

Professor of 20th Century European & American Art

Hunter College

Ara Merjian

Assistant Professor of Italian Studies and Art History

New York University

BRAUN: When Don Draper catches himself looking at the window, and of course his reflection is dead center between the two mannequins, it evokes de Chirico’s pictures and the power that the mannequins have in them.

MERJIAN: Giorgio de Chirico was a Greek-born artist of Italian descent who was the pioneer of what is known as metaphysical painting, which became largely, hugely influential on surrealist art.

B: De Chirico was born in Volos, Greece, the mythic departure point of Jason and the Argonauts. He was schooled in ancient Greek and Latin, and modern Greek as well, and he was surrounded by the ruins of ancient classical Greece. His father was actually in Volos because he was heading up the building of the railroad in that area of Greece. So from the very beginning de Chirico was faced with this schism, this sense of disjuction between the inroads of industrial modernity and the classical past. Much of his work, if not all of it, is about the fact that we can never recover the past, it’s gone forever, so it appears in de Chirico’s work in the form of fragments, specters, things that look generally ancient but we can’t actually identify where they’re from.

M: Being of Italian descent and of Greek birth, de Chirico felt that he had a particular purchase on the classical world, the mythological world, and this informed his entire approach to modernity, an approach that was always filtered through a certain connection with antiquity.

B: De Chirico’s view of humanity is rather a perplexing one. He and his brother referred to themselves as “wandering Jews” in the way that they lived throughout Europe and never really settled down. They were raised Catholic; not particularly religious at all. And as Nietzscheans, as those who read Nietzsche closely, they felt the nature of modern life was that there were no absolutes any more, no guarantees, no solid ground of reason. And reading Nietzsche, de Chirico realized that in fact we just live on the brink of the abyss; we have to construct our own reality.

M: De Chirico really gleaned the idea of space and architecture as a kind of philosophical metaphor. Isolated, solitary, stripped of any reference to particular history, rendered untimely, a word very dear to Nietzsche, something that is against it’s own age, out of season, out of time. And de Chirico applied that to his representations of the world, in which elements of modernity and antiquity are unrecognizably fused, juxtaposed, combined.

B: And de Chirico, from about 1911 through 1918 was painting pictures that are the ones that we’re all familiar with, that are permeated with a sense of enigma and of a natural stillness—the sense of déjà vu, of the uncanny, of something that’s about to happen, a sense of presentiment or foreboding. And the surrealists saw these images not knowing the artist; they began to see them in 1918, 1919, in Giam’s gallery, in exhibitions in Paris, and published in certain journals. They were infatuated with these images because they seemed to be representations of the dream, and the surrealists were heavily invested in their idea of the dream.

M: He had a somewhat short-lived and ill-fated rendezvous with the surrealists when they adopted him and dubbed him as the honorary godfather of surrealist painting. And their interpretation of his work, and of what painting should be in general, soon chaffed against his conception of metaphysical aesthetics. And when he came to renounce his early style, which they had so devotedly latched onto, they felt it was a complete betrayal of his early genius and its contribution to the surrealist imagination.

B: So he never called his work in any way or fashion surrealist, but it’s his early work that the surrealists collected and picked up on, and saw as the model for their own dream imagery.

M: Metaphysical art is a mode of painting, and also to some extent a kind of theory that’s attached to it, of the physical world, in a way that would endow it with metaphysical insight.

B: And for de Chirico the idea of the metaphysical was to create a sense of the enigma, to create in the viewer a sense of surprise and mystery, but in the world of the everyday. So he sought to make everyday objects that are seemingly banal and ordinary that we’re used to all the time suddenly strange and mysterious.

M: Statues figure in even the earliest metaphysical canvases by de Chirico, and from early on oftentimes the statue and the lone human figure are in fact almost indistinguishable. A number of his earliest canvases, like “Autumnal Meditation” and “The Enigma of the Hour” feature isolated, meditating philosopher-types who are almost confused with lone, solitary statuary.

B: We look at these images by de Chirico of these empty Italianate squares with these long arcades and facades of certain buildings and we see that they’re empty yet populated by statues or shadows cast by unseen objects. These statues that populate these empty squares are sometimes seen from behind or from the side, and when de Chirico depicts statues from behind he’s adding to that sensation of mystery which we often have when we turn a corner, we think that there’s a person there, then we discover it’s actually a statue, an inanimate thing that suddenly seems extremely alive.

M: The use of the mannequin as a kind of doppelganger or double or uncanny stand-in for the human is something that has a long history in both art and literature. In modernist avant-garde painting before World War I, it really had yet to appear extensively. In de Chirico’s paintings were really the first few times that the mannequin appears repeatedly as a motif in its own right. There was of course cubist painting which reduced human form to a kind of skeletal anatomy, but de Chirico was really the first to explore the mannequin as the “protagonist,” if you will, of these images.

B: He begins 1914 with his first stitched dressmaker dummy, or mannequin, and then he moves on to variations of the same mannequin, usually the bust-length or full-length figure. Sometimes he adds what seems to be classical armor onto it of some kind. But the mannequin, like the statue, is another form of human simulacrum, something that seems to be alive but isn’t, something that seems to be a stand-in for someone. And the mannequin, like the statue, plays on our unconscious knowledge of doubling, the doubling of self and of other. And of course when you think of things doubling it could become quite sinister in a way.

M: We think that they were inspired, at least initially, simply from the mannequin figures that he would have seen in shop windows in Paris which abounded on city streets, and which were the subject, for example, in Eugène Atget’s photographs during the same years, the 1910s. And here in the shop window, isolated and bathed in light separated out from the street were these human figures that were at the same time objects, individuals that were at the same time things.

B: But there’s a big difference between the statues, which are commemorative monuments, and mannequins, which were developed for something completely different. That is, for the display and advertising and selling of objects, usually personal objects of dress of some kind, or wigs or hair or clothing. And de Chirico seizes on the mannequin in this way because it is something that we associate with commodity culture, with modern culture, so it’s that much more modern than the ancient statue, and they both contribute different effects to his work. Therefore the works are in fact quite theatrical, they’re very much staged in the same way that he said window displays in the great department stores were like little theaters with the curtains always open. He perceived of his pictures as theater, as mise en scène of something about to happen, catching the viewer by surprise; yet he also wants to beguile the viewer and have people enter into the picture and contemplate the images and be transfixed by them and also have the same strong sensation that he feels is the nature of metaphysical painting. That is, the idea that what we thought was real is actually unknowable, something we took for granted, we realize that we don’t know it all, be it a bunch of bananas, a piece of classical statuary, or a pair of sunglasses on a classical marble bust. And of course that juxtaposition of black sunglasses on a classical marble bust is a trope of modern advertising, but we see it first in de Chirico, again, this bringing together of things that don’t normally belong together, to create a new, heightened sensation.

M: De Chirico’s relationship to modernity, as to modernism, was a very ambivalent one, even as he arrived in Paris and gleaned a lot of lessons from avant-garde and modernist painting. The painters Matisse and Picasso were painting, oftentimes only blocks away. He also held at bay a number of elements of modernism and modernist painting.

B: In his autobiography he places himself and his brother in the role of Castor and Pollox who were along in the quest for the Golden Fleece, and he peppers his autobiography and his work with autobiographical references that suggest mythic illusions and mythical gods and narratives from the past. He uses these, which once upon a time were the basis of everyone’s knowledge, literate or illiterate, just like the Bible was as well later on. Yet he’s making us aware that this universal ground of knowledge is no longer applicable to the 20th century. People don’t know their Bible anymore; even more so, they don’t know their ancient Greek myths. So this form of unified culture is lost to us in modern times. De Chirico’s use of myth is therefore highly modern, he renovates it in a way because he makes us aware of how myth functions in the past and how it is today, and he very much sees modern advertising as the modern myth.

M: At one point in the ’20s he writes about the shop windows of Paris that even Homer is re-born in the windows, the shop windows of the Galeries Lafayette.

B: He says when he walks through the streets of Paris, this city which is full of grayness, the gray buildings, the gray climate, yet all of a sudden these apparitions appear: the giant baby of Cadum Soap; the red horse of chocolat Poulain. And window displays: he says window displays of the department stores at the Galeries Lafayette are like little theaters with the curtains constantly opened. And then he relates this to modern myth. He’s basically saying that these images now, which are advertising things, in creating desire in people, are the new myths of modernity. The Mad Men season 5 poster is really a hybrid of de Chirico’s mannequin imagery, and the photographs of Eugène Atget, a very important late 19th, early 20th century French photographer who in the 1920s did a famous series of photographs of the mannequins in the window, which play not only on the uncanny sense of mannequins with painted faces looking out at us, seemingly catching our eye, but also play on the multiple reflections of the glass windows. That is, whoever’s looking into the window—and we’re observing someone looking into the window—they are being doubled by virtue of their reflection, just like the mannequins are already a double or a simulacrum of the human being.

M: We have Don Draper faced with a kind of, to some extent, a metaphysical version of himself. Here is his humanity stripped bare, rendered an object.

B: It’s fascinating to consider that as the viewer we see Don Draper looking at himself in his reflection, but also looking at the scene in front of him. It’s ambiguous; of course ambiguity is typical of de Chirico, that adds to the enigma. But the expression on his face in that poster image is not one of irony or even self-doubt. His eyebrows are a little arched, which suggests that he’s been pulled completely into the scenario that is there in front of him. And what is the scenario? It’s a seated man, elegantly dressed in his robe, and he’s looking admiringly at a woman who’s totally nude, in fact she’s just dropped her dress there. And her arm gestures are such that she’s presenting herself to him for his appraisal, for his judgment. And it’s quite fascinating, because this relates to de Chirico; de Chirico writes about department store windows, particularly ones in the Galeries Lafayette. And he remembers one in particular that’s advertising summer fashion, that is beach fashions, and he said there was a strange gentleman, phantom-like baby, seashells, towels in the sand, and then a painted cloth backdrop, dark blue and light blue. And all of this, de Chirico says, reminds me of Ulysses’ constant voyages. Now, if you look at the Mad Men season 5 poster, what myth does that remind us of? It reminds us of the Judgment of Paris, which is the story of a banquet that Zeus throws in honor of Peleus and Thetis’ marriage; they would be the parents of Achilles. And Eris the goddess of discord was not invited, because naturally she would’ve made things unpleasant for everybody. Snubbed, she shows up nonetheless and she throws this golden apple in the midst of the party, which is inscribed “To the fairest.” And immediately the three goddesses, Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite start bickering about who the fairest is and who should get the apple. And then they call upon this Trojan Paris, a mortal, to make the judgment of which of the three goddesses is the most beautiful. Eventually he chooses Aphrodite because she promises Helen of Troy as the prize. But in any event, the point of the story, as in the image of the poster, it’s just like images in many paintings in the history of Western art of the nude goddess standing like so in front of Paris to be judged. And that’s what’s happening in that image. And Don Draper of course puts himself, he imagines himself, I presume, in that position of judging.

M: With regard to Don Draper as an enigma, he certainly has elements of that thorny, barbed, and yet entirely attractive element of an enigma; he is hermetic, which the art of de Chirico absolutely exemplifies.

B: I think that Don Draper thinks that he’s an enigma. I think that Don Draper is probably extremely self-possessed in his life and knows that he’s alienated from friends, family, co-workers to a certain degree, so I think he is very self-conscious of himself being an enigma.

For a full-size version of the Mad Men season 5 poster (full HD, 1920 x 1080), perfect for Windows wallpaper background on a wide-screen monitor, click HERE, and when the window opens right-click and “Save As”. (Large file, about 1.1 MB)