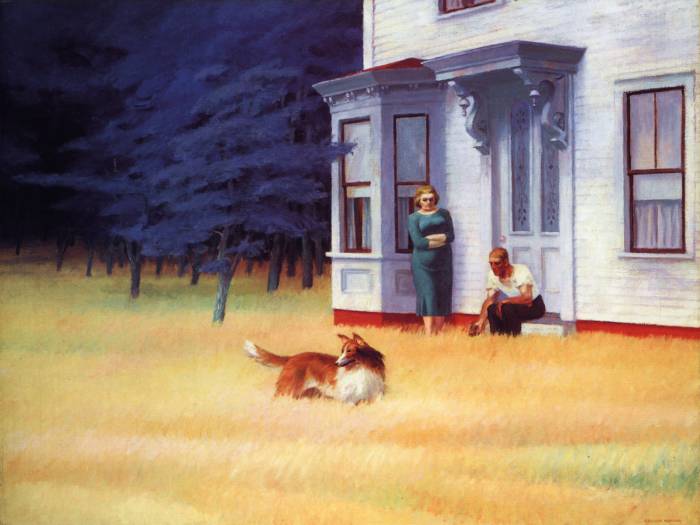

Cape Cod Evening

Edward Hopper, 1939

Cape Cod Evening

Edward Hopper, 1939

In his art Hopper reflected on progress, its beneficiaries and its victims. In this painting the couple belongs to the latter group. Their yard has become a field that is in the process of being overrun by locust trees, and the couple huddles near a grand house that seems alien to them—a house that belongs to another era and bespeaks a refinement that is inconsistent with their work-worn appearance.

Hopper’s great culminating picture of Cape Cod in the 1930s is CapeCod Evening (1939). In the ledger book, Jo [Hopper’s wife] notes:

Cape Cod Evening—finished July 30, 1939. Note design on glass door and house. Young man... good looking Swede. Was to have been called “Whipporwill” [sic] Dog hears it.... Woman a Finn & dour. Trees in phalanx position, creeping up on one with the dar[k]. The Whipporwill [sic] is there out of sight. Painted in S. Truro Studio. (Vol. II)

Lloyd Goodrich has quoted Hopper’s own account of the painting:

It is no exact transcription of a place, but pieced together from sketches and mental impressions of things in the vicinity. The grove of locust trees was done from sketches nearby. The doorway of the house comes from Orleans about twenty miles from here. The figures were done almost entirely without models, and the dry, blowing grass can be seen from my studio window in the late summer or autumn. In the woman I attempted to get the broad, strong-jawed face and blond hair of a Finnish type of which there are many on the Cape. The man is a dark-haired Yankee. The dog is listening to something, probably a whippoorwill or some evening sound.

Several aspects of both descriptions need to be elaborated on: (1) the scene is late summer or autumn, (2) the couple is of immigrant stock or a mixture of immigrant (the man who may be Swedish and the woman who is definitely Finnish) and local (the man whom Edward Hopper refers to as “Yankee”), (3) the dog responds to the sound of the whippoorwill outside the painting, and (4) nature is once again taking over: the trees are regarded as a phalanx, and night is approaching.

Cape Cod Evening is concerned with the loss of a viable rural America: it focuses on those people and places that have been left in the wake of progress. Today it is rarely remembered how enormous were the differences between the rural and urban population in the late 1930s. At that time three out of every four farms were lit by kerosene lamps, a quarter of the rural homes lacked running water, and a third were without flush toilets. Cape Cod Evening was created the same year as the New York World’s Fair, which was entitled The World of Tomorrow. The fair featured a robot called Elektro, which could talk and smoke, and an exhibit organized by GM entitled Futurama. Designed by Norman Bel Geddes, the GM exhibition drew twenty-eight thousand paying customers a day who sat on a conveyor belt armchair for fifteen minutes and listened to a recorded voice explaining what the American landscape would be like in 1960. To a generation that had been burdened by the Depression, Bel Geddes’s predictions were less important for their accurate forecasting than for the fact that he was offering people an opportunity to begin thinking optimistically about the future.

In Cape Cod Evening Hopper creates a complete contrast to The World of Tomorrow by picturing a future that is retrograde. He shows how nature is reclaiming land, which less than a century before had been domesticated into the site of an imposing Victorian house with its attendant garden. Although the collie in the preliminary drawing for this painting is turned toward the couple, in the completed painting it directs its attention to the sound of the whippoorwill, which symbolizes the power of nature over culture. The Victorian house is shown standing in a field of grass; it has lost its lawn, and locust trees have advanced to the house and are in the process of taking over. The woman appears uncomfortable in the grass. Dressed in a modish streamlined style, which is inappropriate for her very full figure, she is a composite of misaligned signs. Her Rubensian figure might have made her a candidate for a fertile earth mother in another era, but in the 1930s she symbolizes nature overgrown and ill at ease with itself, nature corseted and wearing bobbed hair. The onlooker to this scene is probably a local who is familiar with the lay of the land, a person who would note that the trees are locust and who thus differs from Hopper’s usual observer, the motorist from a metropolitan area who regards all flora and fauna generically. The change in orientation is idicative of Hopper’s own situation, for he had built a place in South Truro in 1934 and spent six months out of almost every succeeding year of the rest of his life on the Cape. His new orientation made him increasingly alert to the problems of people in the country who frequently did not have basic modern amenities and who were suffering from a sustained economic depression that extended years beyond the Great Depression.

Cape Cod Evening constitutes a new paradigm in American landscape painting, for it emphasizes the passing of the agrarian age and the forlorn individuals who become idle caretakers of an anachronistic way of life. While Early Sunday Morning permits a positive reading of the role of the small businessperson in reorienting the economy of the United States, Cape Cod Evening does not allow any such approach. The couple seen in this painting could inhabit House by the Railroad. The difference between both pictures is that the conflict is no longer between new modes of transportation and old-world culture: the conflict is between obsolete lifetyles and nature. This theme had been briefly presented in American art in the 1860s when abandoned mills were viewed as romantic ruins by David Johnson. But his pictures do not constitute the new paradigm represented by Cape Cod Evening because they become suffused in nostalgia and in a delight in history that is affirmative and that differs from the pessimism of Hopper, who pictures a forlorn couple out-of-character with its grandiose Victorian house and intimidated by the unruly nature outside. The importance of this picture and Hopper’s other Cape Cod scenes can be gauged by the fact that they served as influences for many paintings by Andrew Wyeth, particularly his series of works on the Kuerners and the Olsons. The couple of Cape Cod Evening could be considered a source for Christina and Alvaro Olson, and the house a basis for the paintings Christina’s World and Weather Side.

—from Edward Hopper, by Robert Hobbs