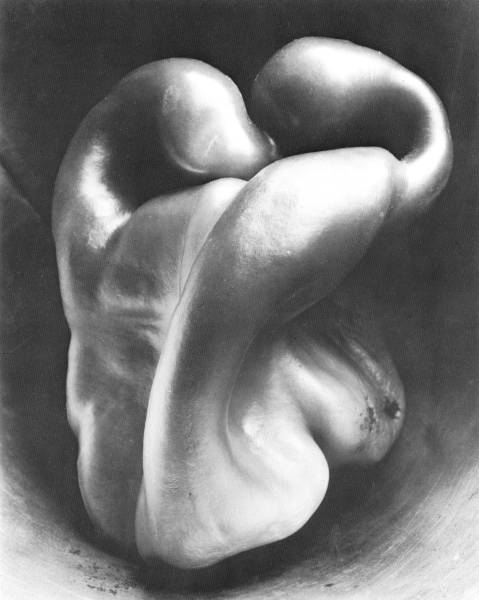

Pepper #30

Edward Weston, 1930. B & W photograph.

Pepper #30

Edward Weston, 1930. B & W photograph.

Clouds, torsos, shells, peppers, trees, rock, smokestacks are but interdependent, interrelated parts of a whole, which is life.—Life rhythms felt in no matter what, become symbols of the whole.

—Edward Weston, April 24, 1930

I could wait no longer to print them—my new peppers, so I put aside several orders, and yesterday afternoon had an exciting time with seven new negatives. First I printed my favorite, the one made last Saturday, August 2, just as the light was failing—quickly made, but with a week’s previous effort back of my immediate, unhesitating decision. A week?—yes, on this certain pepper—but twenty years of effort, starting with a youth on a farm in Michigan, armed with a No. 2 Bull’s Eye Kodak, 3-1/2 x 3-1/2, have gone into the making of this pepper, which I consider a peak of achievement. It is classic, completely satisfying,—a pepper—but more than a pepper....

—Edward Weston, August 8, 1930

Is Edward Weston’s photograph of a green pepper meaningful to us because we like peppers so much? I think not. Weston has been able to create meaningful form on a surface with the help of a pepper. It is his sense of form that tells us how deeply he has experienced this pepper.

By exercising critical selection every step of the way, Weston finally achieved his goal of “significant presentation of the thing itself.” Weston felt strongly that he wanted to present, rather than interpret, the many natural objects he was working with at the time. He wanted to record his feeling for life as he saw it in the “sheer aesthetic form” of his subjects. In doing so he revealed with clarity and intensity what was there all along.

—from Man Creates Art Creates Man, by Duane Preble

|

Vegetable Crisper: Group Portrait With Bell Pepper

Huddled alone

|

Notes transcribed from an old 1970s documentary film, “The Photographer”

Most of us know how to point a camera and snap pictures of things that give us pleasure: the new, the quaint, the odd. A fiftieth of a second of sunshine is enough to produce an image that we can fill in later from memory. The funny faces that recall the laughter.

But the student of photography thinks that a camera is more than just a device to jiggle the memory. Like a painting or a poem, a photograph can be an experience in itself. It can be the end to which the artist uses in seeing the beauty about him.

Such an artist is Edward Weston. To study photography with Weston is an opportunity to learn about art itself. The things around his house show signs of a personality distilled out of a full, rich experience. The things around his room are all fragments of things he has seen, and felt, and known: the beauty to be found in nature, Mexico, friends. He seems to like simple, uncomplicated things that most of us can understand and like.

Weston believes his photographs must reflect what he thinks about the world around him. His inclination is toward nature and toward the earth. He sees dignity and strength and beauty in the long rows of a giant California farm. He doesn’t believe that man must scar the face of nature to use her well. But what does all this have to do with photography or art? Just this: that the artist is first a man, and into his art he can only put what he feels and thinks as a man. To know what Weston likes is to know how he chooses the subject of his photograph. His greatest pleasure is the simplest of all: the pleasure of looking at the varied scenery of California.

His most important tool is not his camera but his eye; for the artist is first of all a selector, a searcher. He is a man who can search energetically and patiently, who has the integrity to search for what pleases him, not for what he thinks will please others.

Behind Weston’s selection of a subject lies the emotional experience of a lifetime. He has long since found out where to look and how to look. He has a knowledge of his camera’s powers and its limitations. It’s a machine that operates by light. So the quality of the reflected light that the photographer can see on his ground glass is a factor that he considers when making his selection. Weston has no rules for lighting. He simply looks for the light that will best reveal the nature of the material he is photographing. He uses an old fashioned view camera because it enables him to observe the most minute detail of the scene before him.

The lens is the camera’s eye, and like the human eye it enables us to be selective, to pick out those sections of a total scene on which we wish to concentrate. And what are those sections? The ones that please us. Why do certain forms please or interest us? No one knows, not even the artist. The forms, the lines, the shapes that affect Weston’s feelings often reappear in widely different subject matter. The reason why we like things are often buried deep within our subconscious mind, stemming perhaps from some long forgotten experience in our childhood, or answering a need that we ourselves do not know we have.

That’s why in looking at Weston’s photographs it is often interesting to forget what they are about, to ask not what is this a picture of, but what does this shape remind me of, how does it make me feel? For Weston is not only telling us what a particular rock or flower or bird looks like, but also what it means to him. If we do not catch his feelings most of his message is lost, for his photographs, like all art, communicate both thought and feeling.

Because Weston does not trim his pictures nor enlarge them, what he views on the ground glass is also the moment of final selection: what instant to catch and make permanent, what particular section should fill the space. In the artist’s approach to photography there are no rules to composition. Because each picture presents its own problems he can use no shortcuts, no formulas. The answer must be worked out on the ground glass each time all over again. But how do we know when we’ve solved it? Can there be more than one answer? Perhaps. And the artist who can see and feel can recognize each one that’s right for him.

What a man sees when he looks at any subject matter is determined by his imagination, training, the sensitivity of the mind behind the eyes, and by what he knows and feels. Weston has the essential qualifications, and he knows his equipment. He uses a photoelectric cell to measure light, close-up lenses to bring distant objects closer, reduces the aperture to focus both foreground and background, and inserts a filter to change light values for certain effects like a darkened sky.

This attention to detail, this care and accuracy, this technique is what produces art in any medium, but only when it serves the feelings and the knowledge of the artist. This is the hardest part of the apprenticeship to art: to open our hearts so that we can feel freely, to clean up the clutter of our minds so that we can think clearly. No teacher, no master can tell us what to look for in the world around us, how to evaluate what we find. They can encourage our patience, our inquisitiveness, our right to have our own feeling and our own ideas, but we must do our own work. What we do not think or feel is not likely to appear in our pictures.

Now that we know how Weston works, we can appreciate what goes into his creative process: an intense love for the world around him, the sharp eye attuned to the mind behind it, the constant search for significant form, the need to find order in what first appears to be chaos, and finally the discipline of technique, the painstaking skill of a master craftsman. These things make a photographer an artist. They lift him out of the role of recorder to the heights of creation.

For Weston, imprinted negatives have the attraction and drama of hidden treasure. The darkroom is the setting in which the photograph finally comes to life. Weston’s darkroom is as old fashioned as his camera. He doesn’t have any devices unknown to photographers fifty years ago. He just uses the simple equipment with infinite skill. Weston is willing to repeat any process many times to get it right. Art cannot afford compromise.

Weston is only one of a line of distinguished artists who use the camera as a creative tool. The French painter Louis Daguerre did photographic experiments with still life subjects as early as 1837. Paul Nadar, another Frenchman, was attracted by the formalism of his time, but his photographs were pictures of real people. The first to exploit the camera’s special powers of precision and accuracy was the American, Matthew Brady. He refused to prettify Abraham Lincoln’s noble homeliness, but his portraits reveal the beauty of character within the great emancipator. Brady followed the Union army, and, with primitive camera and wet plates, he combined art and journalism. His portrait of Walt Whitman is a record of a poet’s personality.

The principles of looking for beauty in the ordinary backgrounds of modern life was also being developed at the turn of the century by Alfred Stieglitz. With his learned arguments and his beautiful pictures Stieglitz once and for all settled the question: is photography art? Today that question is no longer debated.

Men like Edward Steichen, Paul Strand, Ansel Adams, Walker Evans, and Weston himself, do not have to fight for recognition or appreciation. They do not have to come to us, we are more than willing to go to them.