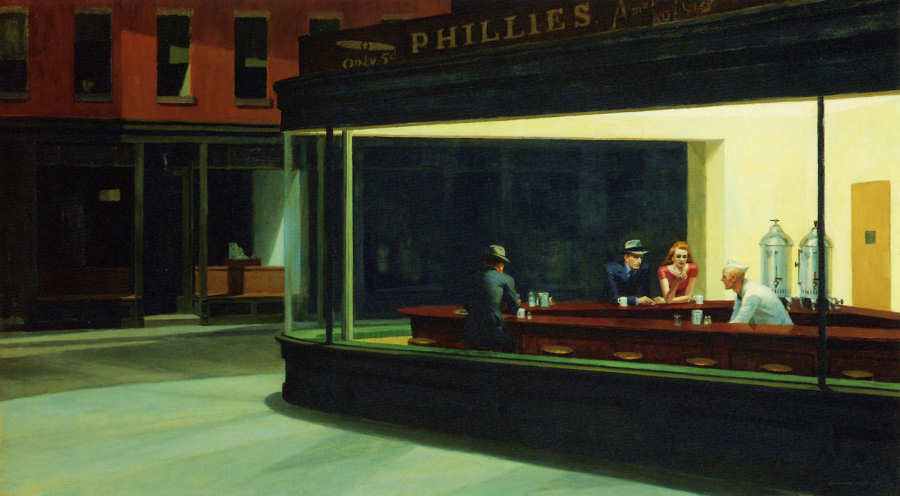

Nighthawks

Edward Hopper, 1942

Nighthawks

Edward Hopper, 1942

Nighthawks (1942), a picture of a diner at night, continues Hopper’s concern with small-time businesses that was first established in Early Sunday Morning. The background of Nighthawks, in fact, consists of a row of stores that resembles those pictured in Early Sunday Morning. This background serves the psychological function of emphasizing the coldness of the diner in Nighthawks. The customers seated around the counter do not seem to be the kind of people who would operate the businesses on the opposite side of the street. The old-fashioned cash register seen in one of the dimly lit shops conjures up an air of familiarity and affability; it suggests a family business that has been in operation for a number of years and has been successful enough not to feel the need to modernize the store in order to keep customers. In contrast to the stores, the diner is lit with the new fluorescent lights that had only come in use in the early 1940s. Circular in form, this building is an island that beckons and repels; and the fluorescent lighting is intimidating, alienating, and dehumanizing. It creates an unreal and artificial feeling of warmth, an atmosphere that is clinical and more in tune with a laboratory than a restaurant. In conversation with Katherine Kuh, Hopper reflected that the scene for the painting “was suggested by a restaurant on Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet.” He said, “I simplified the scene a great deal and made the restaurant bigger. Unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.” Jo’s [Hopper’s wife] entry in the ledger provides insight into the meaning of the diner and the people stationed within it:

Nighthawks—night & brilliant interior of cheap restaurant.... Cherry wood counters & tops of surrounding stools, lights on metal tanks at rear right; brilliant streak of jade green tiles 3/4 across canvas at base of glass.... Very good looking blond boy in white (coat, cap) inside counter. Girl in red blous[e], brown hair eating sandwich. Man nighthawk (beak) in dark suit, steel grey hat, black band, blue shirt (clean) holding cigarette. Other figure dark sinister back—at left.... Darkish old red brick houses opposite. Sign across top of restaurant shop dark—Phillies 5¢ cigar—picture of cigar.

When one looks closely at the heads of the man and woman facing the viewer, their faces are amazingly hawklike. The title Nighthawks can refer to people who are night owls, but it also refers to a particular kind of nocturnal bird (genus Chordeiles), which is related to goatsuckers and whippoorwills. The relationship of the nighthawk to the whippoorwills suggests that this painting may be the urban pendant to Cape Cod Evening in which the collie responds to the song of the whippoorwill. Whereas in the latter painting Hopper shows how nature is taking over, in the former, Nighthawks, he pictures a diner that represents a move toward a mechanized future and people who still exhibit an untamed restlessness. Both situations are regarded with a jaundiced eye: nature and technology attract and repel at the same time.

The figures in Nighthawks could be characters in a Dashiell Hammett story. They are quiet and deliberate. Despite the number of writers who describe this painting as a meditation on desolation and loneliness, the couple appears to be completely attuned to each other. Their gestures complement one another’s, and their arms and shoulders form a cohesive trapezoid that bonds them together. The feeling of desolation in the painting may stem from the architecture of the diner, the lurid lights, and the mysterious presence of the third customer. In addition, the feeling of loneliness may have originally derived from the fact that Nighthawks was created the year after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entry into World War II, a time when young men were sent off to the armed services and the entire country was caught up in the war effort. The fact of the war causes one to wonder exactly who the Nighthawks really are. They do not seem to be local businesspeople, and they are certainly not military personnel. They appear to be outsiders, a fact underscored by the architecture and lighting of the diner, which separate them from the surrounding community of buildings.

The viewer of Nighthawks becomes another nighthawk, another creature who is unconnected to the reality of the war and who swarms around the brightly lit interior of the diner that both repulses and attracts and ultimately provides no possible means of entry.

—from Edward Hopper, by Robert Hobbs

Apparently, there was a period when every college dormitory in the country had on its walls a poster of Hopper’s Nighthawks; it had become an icon. It is easy to understand its appeal. This is not just an image of big-city loneliness, but of existential loneliness: the sense that we have (perhaps overwhelmingly in late adolescence) of being on our own in the human condition. When we look at that dark New York street, we would expect the fluorescent-lit cafe to be welcoming, but it is not. There is no way to enter it, no door. The extreme brightness means that the people inside are held, exposed and vulnerable. They hunch their shoulders defensively. Hopper did not actually observe them, because he used himself as a model for both the seated men, as if he perceived men in this situation as clones. He modeled the woman, as he did all of his female characters, on his wife Jo. He was a difficult man, and Jo was far more emotionally involved with him than he with her; one of her methods of keeping him with her was to insist that only she would be his model.

From Jo’s diaries we learn that Hopper described this work as a painting of “three characters.” The man behind the counter, though imprisoned in the triangle, is in fact free. He has a job, a home, he can come and go; he can look at the customers with a half-smile. It is the customers who are the nighthawks. Nighthawks are predators—but are the men there to prey on the woman, or has she come in to prey on the men? To my mind, the man and woman are a couple, as the position of their hands suggests, but they are a couple so lost in misery that they cannot communicate; they have nothing to give each other. I see the nighthawks of the picture not so much as birds of prey, but simply as birds: great winged creatures that should be free in the sky, but instead are shut in, dazed and miserable, with their heads constantly banging against the glass of the world’s callousness. In his Last Poems, A. E. Housman (1859-1936) speaks of being “a stranger and afraid / In a world I never made.” That was what Hopper felt—and what he conveys so bitterly.

—from Sister Wendy’s American Masterpieces, by Wendy Beckett