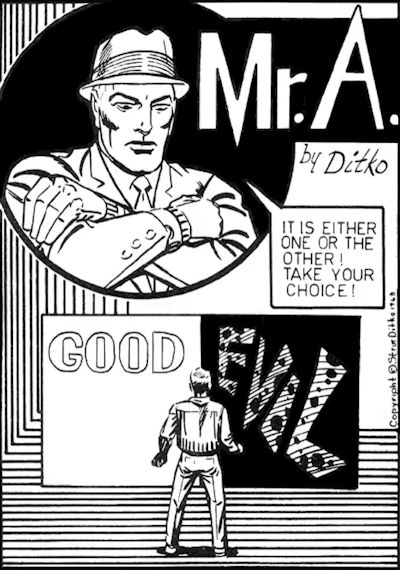

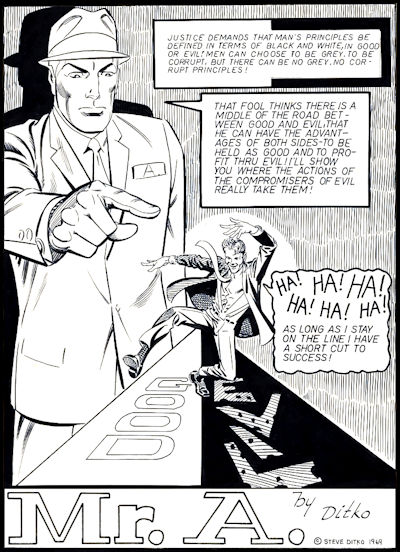

Mr. A

by Steve Ditko

Mr. A

is based on Ayn Rand’s theory of justice, on Aristotle’s law of identity, his definition of man, and his view of art. Aristotle said that art is philosophically more important than history. History tells how man did act, art shows how men could and should act. Art creates a model, an ideal man as a measuring standard. Without a measuring standard, nothing can be identified or judged. But everything can be measured. Disease and sicknesses are measured by a healthy organ or body. All measurement requires an appropriate standard. With it, one can measure down to atoms, up to the stars, and the changes in the character of a man.

Aristotle defined man as a rational animal. Rationality is a potential that has to be actualized, by choice and the right thinking method of logic applied to reason. The standard of measurement for all is a rational, logical ruler. It objectively measures the rational and irrational thinking. A hero measures a man at his best in the worst situation. A hero is a man admired for his qualities or achievements and regarded as an ideal or model.

Aristotle formulated the Law of Identity, A is A,

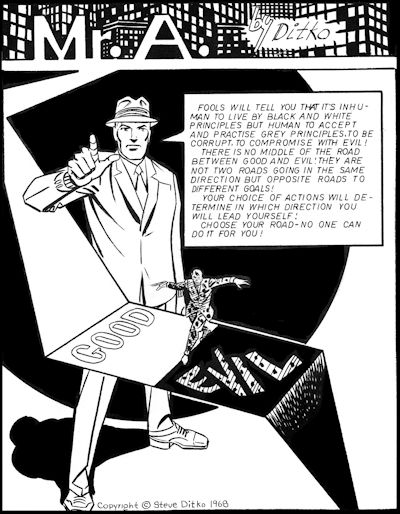

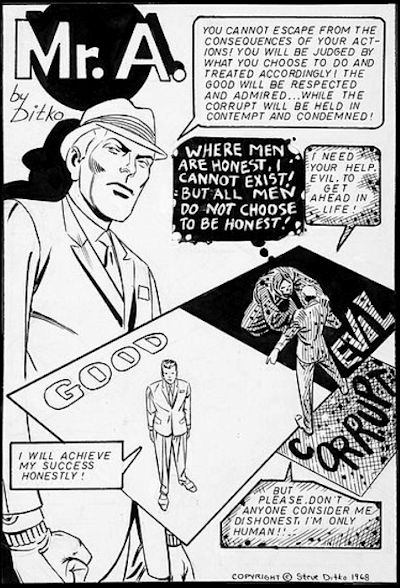

a thing is what it is; it has a specific nature and identity. The truth cannot contradict itself and also be a lie. Mr. A’s black and white card symbolizes the Law of Identity. It identifies the two moral potentials possible, the good and the evil, and by one’s chosen action the best or the worst potential can be actualized.

The card is also a symbol of justice. For Ayn Rand, justice is objectively identifying a thing for what it is, and treating it accordingly. No one gets the unearned. The innocent is not penalized, the guilty is not rewarded. The card is a refusal to violate the root of justice, the Law of Identity, by a gray compromise; a refusal to sacrifice the good to the evil, or to accept any part of the evil as a greater good.

Society has its admirable people, its heroes; they are found in all professions. But hidden by the complexities of society, they are not as clearly defined, not as understood, and not as effective a model as a story with two opposing forces of right and wrong in a dramatic presentation revealing the characters choices and actions that identify them and lead to a just ending where the hero and the right view of life wins.

Early comic book heroes were not about life as it is, but creations of how a man with a clear understanding of right and wrong and moral courage chose to act even if branded an outlaw. He dispensed a better justice than the prevailing legal moral one. He was a moral avenger. He was not like everyone else; not the average, the common, or the ordinary man. He was the exceptional one, the uncommon one, the one doing what others were unwilling to do, regardless of the opposition and consequences to himself. His success provided a better model.

Through a hero, one could identify the foolish, the corrupt, and the guilty. A lead character can be better or worse than society’s best model, and if a man with proven better qualities appears, then a new measuring standard for man and society is established. A hero is a model for everyone, but not everyone is willing to act at his best. A less demanding model, blending good and bad, is more comforting, easier to accept. For the self-flawed, an anti-hero provides an heroic label without the need to act better. A crooked cop, a flawed cop, is not a valid model of a good law enforcer. An anti-cop corrupts the legal good, an anti-hero corrupts the moral good. Both corrupt ideals; both choose the flawed over the perfect. The perfect is identified and measured by what is possible to man—a perfect bowling score, etc. A perfect response accepts the truth and rejects the lie. The perfect hero on principle says yes to a true identity and no to a contradictory one. Ruled by justice, he treats every identity as it deserves. He is the actualized potential for good in its purest form, a true moral measuring ruler. He is the most human, and deserving of respect.

Today’s flawed superheroes are superior in physical strength but common, average, ordinary in mental strength; rich in super powers but bankrupt in reasoning powers. They are perfect at overcoming the flawed super villains, saving the world, the universe; yet helpless to solve their common, ordinary, average personal problems. It is like creating a physically perfect adult with the reasoning limits of a six-year old. The creators of flawed ideals believe that no real difference exists between a flawed hero and a flawed villain. Both have some good and some bad in them, so they blend into a grayness where no one is better than anyone else and where the worst can justifiably claim that he is as good as, as gray as, the best.

If it is impossible to know what is true and to do what is right, then the flaw, the worst, will be the new standard of good. Man will be defined as a flawed, antirational animal, and all that corrupts and harms life will be the new virtues. Like deliberately flawed eyesight, where self-blindness is the ideal, anti-life behavior will be the new standard for living. The resentment against the perfect hero is a resentment against A is A,

against the integration of truth and behavior, against the non-contradictory identity of a moral ideal, against reality and life’s measuring ruler, a rational moral standard.

The above text was transcribed from one segment of a very old VHS videotape, Masters of Comic Book Art. They were Steve Ditko's comments on "Mr. A," the comic book character he created in the late 1960s. "Mr. A" was not just the proverbial fighter for justice and avenger of evil. Instead of a normal business card, his calling card was simply one-half solid black and one-half solid white, representing good and evil.

Without specifically mentioning it, Ditko perfectly explained why modern American movies are the worst kind of true Art with a capital A, and why the liberalism that has taken over Hollywood since the late 1960s prefers flawed anti-heroes now instead of heroes like John Wayne or—a perfect example—Paul Scofield in A Man for All Seasons.

Of course a hero is "larger than life" and "unrealistic;" they're supposed to be. A hero is a perfect ideal you look up to and try to emulate. An anti-hero is just like you and me, no better, no worse.

If no one is any better than anyone else, then how dare you judge someone else. That's why everyone today is so quick to openly express the lunatic idea that "you shouldn't be so judgmental." I say exactly the opposite. If no one judges anyone anymore, you can do anything you want and not be looked down on or shamed or embarrassed by society's judgment. It's a convenient way of doing whatever you want in life and never taking any blame for it; it's always someone else's fault. (Hey, you have heart disease because you've been so fat for 30 years? Sue McDonald's! You have lung cancer because you've been a heavy smoker for 30 years? Sue the tobacco companies because the warning on cigarettes wasn't in large enough type!)

You never have to put out any effort to live up to a standard, and your precious little wimpy feelings will never be hurt by people judging you to be at fault because you have done something wrong, because hey, there is no right or wrong....

—Zimmerman Skyrat, 101Bananas.com