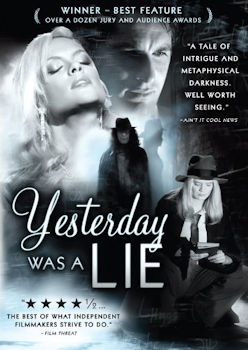

YESTERDAY WAS A LIE

Released: 2008

Written & Directed by: James Kerwin

Cast:

Kipleigh Brown: Hoyle

Chase Masterson: Singer

John Newton: Dudas

Mik Scriba: Trench Coat Man

Nathan Mobley: Lab Assistant

Warren Davis: Psychiatrist

YESTERDAY WAS A LIEReleased: 2008

|

|

Review by Lawrence Cronin, posted at Amazon.com

Yesterday Was a Lie is a love story for cerebral cineastes. It was a delight to watch after dinner with a philosophy professor friend and three glasses of wine, and it belongs right up there with your volumes of Wittgenstein. Upon more sober viewing, my analytic mind felt challenged. Actually, this reflects the film’s purposeful plotting. Being a psychiatrist, let’s see what I can offer.

The film exemplifies Jean-Luc Godard’s famous maxim that all it takes to make a movie is a girl and a gun. In this case the lead female characters are two lovely blondes. Each so cleverly resembles the other that one is reminded of Luis Buñuel’s 1977 surrealist movie That Obscure Object of Desire, where two actresses played one character.

But adding layers of complexity here, these twin-like actresses are also playing the left and right sides of the brain of the feminine anima of one male character. Got that? They all meet at the Pigeon Hole lounge. The first character is the young Hoyle (Kipleigh Brown), a feminine Bogart/Sam Spade analytic detective—the left brain. Like Sam she likes the gin and the story straight. The second is a sultry, un-named singer (Chase Masterson) who has a familiarity with the poetics of T.S. Eliot—the right brain. Her music is entrancing, her wit intuitive and nonlinear. Together, these two provide the counterpoint of Jung’s anima to the male animus of the main character, Dudas (John Newton).

Whether Hoyle and her counterpart, The Singer, convince us they are our anima is irrelevant, as we so want them to be part of us. These lovelies draw us ever so seductively into imagining the dark recesses of our own beautiful unconscious, despite any misgivings. All we’re here for is love, we are told. The shape of the universe is a relationship—functional or otherwise—whether the relationship with our inner parts or with our fellow beings. This makes for a strange little Jungian romp in luscious black and white footage à la Bogart and Bacall. This is David Lynch with an underlying premise. Somewhat like the film Pi (made for $60,000), this low budget beauty was made for about $200,000.

So, have you read Jung, had a few mysterious dreams, find yourself in need of some clues? First time director James Kerwin makes for a Jungian fortune teller taking us on a trip to disentangle or re-entangle our male and female halves. Kerwin is an urban shaman who shows us the conventional mind as a “surge suppressor.” Our conscious minds filter small broken bits of time in a lame attempt to tell a story. Does it matter whether they “add up?”

Beginning with some obvious allegory, the locks are broken off the allegorical unconscious and our character, curiously named Hoyle bravely walks into a poetic film noir journey to confront the Self. (Hoyle seems named after transcendental astronomer/physicist Fred Hoyle who was deeply intrigued by the “Anthropic Principle” of nature.) We begin with a look at Dali’s surrealist masterpiece The Persistence of Memory in a hallway. They meet Schrödinger’s cat, the parable of which tells us there are opposite angles on everything and only by choosing do we arrives at any definitive perspective. Free Will is discussed. The film reveals a Jungian fenestra aeternitatis, a window to the eternal, that our characters need to navigate.

A variety of other cutting edge consciousness theories are peppered throughout the film to spice the intellectual interest of the knowledgeable viewer, including pondering Planck’s constant, a number describing the fundamental vibration at the Ground of Being. For those less informed, the film literally goes back to the psychiatrist to explain itself. Jung, we are told, said a man needs to project his animus onto the feminine anima in order to unlock the secrets of the universe. This is a film for men who are in need of seeing themselves and for women who want a deeper look into those men. What does a man see in himself as a woman?

Hoyle goes into a dream within a dream (hasn’t everyone had at least one of these?) to contact her animus, Dudas, who has a notebook of important thoughts or ideas. Meanwhile we are constantly asked, what if our theories, concepts of self, and common sense don’t add up? And what does that tell us about our relationships? And what is the nature and consequence of the loss of “relationship?” The right-sided feminine asks the questions. Left-sided Hoyle tries to read the tea leaves, the pattern in the chaos. Hoyle and her doppelgänger meet another aspect of their animus, a scientist who explains the nature of time and who feels these two sexy blondes are “better” and “better.” They are also the choices that interface with reality. They will help us overcome our own guilt about our very existence and the broken promises to ourselves and to others.

A deep understanding of time is seen in this film’s Feynman diagram writ large in cinema. Physicist Feynman showed everything else might be one mind/particle bouncing backwards and forwards in time, appearing as each and all of us trying to make contact with every part of experience over eternity, the very fabric of time. This reach for the eternal is countered by the Shadow, the dark side, who delivers a bit of lead poisoning in the form of bullets. Death’s shadow is a terrifying/exhilarating lockdown on the many-sided reality of now, it haunts our Selves. It occurs when we bring our stories to a halt. We need to let go of our life-text and grab onto our fuller selves, leaving our memories to be what they are and move on to script ourselves anew.

This film is an ultimate romance with “The Other,” a mix of the cosmos and the chaos, the order and the disorder, the male and the female. In this cocktail lounge of our emotions, letting go of our primordial selfishness lets our unconscious sing its own songs, reconciling the Self to itself. And pay attention to that terrific music in here. Chase Masterson beautifully sings the lounge songs of our longing.

As T.S. Eliot is quoted:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time

Through the unknown, unremembered gate

And for an alternate point of view, a review by “groggo” posted at IMDB.com

There is such a thing as film noir, but this meandering mess is more noir film. The lush photography resembles a flood of commercials for shampoo or trench coats. It is beyond film noir, so far beyond in fact that I thought at first I was watching a satire or even a parody. Few of the scenes are bathed in anything but heavy, moist black and white, with precious little relief to let the film ‘breathe.’ I think there’s a plot, but it’s so encumbered by pretentiousness that it’s hard to find. This film is far more about style than substance.

If you enjoy a movie that is basically an ode to metaphysics (the search for lost time and space), if you enjoy gabfests about the nature of Jungian ‘archetypes,’ then this movie fills the bill, although I would personally prefer a documentary on the subject. I thought I was watching a seminar at times.

This flick shows us a beauteous babe searching for a (what else?) ‘shadowy’ figure who is lost in time. We hear pretentious references to T.S. Eliot, Planck, and Dali. And when the pseudo-intellectual stuff is not strutting between the endless black-and-white drudgery of the film, you get to listen to grade B dialogue spoken by barely believable actors. One big yawner. I think IMDb’s rating of 5.3 out of 10 is generous.