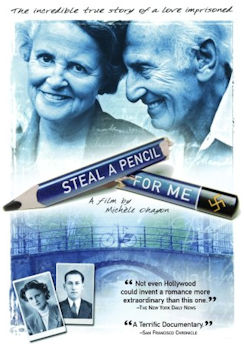

STEAL A PENCIL FOR ME

Released: 2007

Written & Directed By: Michèle Ohayon

Cast:

Jack Polak: as himself

Ina Soep: as herself

STEAL A PENCIL FOR MEReleased: 2007

|

|

Review by Nora Lee Mandel, Film-Forward.com

The Holocaust is overwhelming. So many documentaries numb audiences with the staggering statistics and gruesome catalog of horrors. Even with the worthy post-Schindler’s List efforts to record survivors’ experiences, what can get lost is the distinctiveness of each individual swept up in history’s maw. Steal a Pencil for Me, however, uniquely personalizes the incomprehensible through a love story.

An unhappily married accountant falls in love at first sight with a rich younger woman across a crowded room at a birthday party. It’s June 1943 in Amsterdam, and they both wear the Nazi yellow star for Jews. Jack (Jaap) Polak has already been arrested once, and Ina Soep is pining for her deported brother and boyfriend. A month after he meets Ina, Jack and his estranged wife, Manja, are deported to Westerbork transit camp, originally set up by the Dutch as an inhospitable refugee center for German Jews. Jack finds Ina there in September, after she is also sent to Westerbork.

Filmmaker Michèle Ohayon does a lot more than just tell the fascinating enough story of their clandestine courtship in two concentration camps under the eyes of their disapproving families and gossiping inmates, let alone through Nazi restrictions, deprivations, disease, labor, and the chaos of liberation. Reflecting back and forth between the present and the past, Ohayon combines their vivid accounts, and those of his feisty sisters and her friends, with family photos, meticulous German records, somewhat romanticized recreations, and, acutely, carefully researched archival footage that has rarely been seen outside a few European documentaries.

The centerpiece is their extraordinary love letters and how movingly Ohayon brings them to life. Sneaking surreptitious contact and brief walks together away from her strict relatives and his proud wife, they start a stealthy correspondence through “messengers of love,” which continues even after being separately transported to the even bleaker Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. As their written words flow over the screen in Dutch and are seen being composed on facsimiles of their crude writing materials, Jeroen Krabbe (Soldier of Orange) takes on Jack’s voice, and Ellen Ten Damme voices Ina. (The couple’s daughter, Margrit, a friend of the director, translated the letters for their 40th anniversary, leading to their annotated publication.)

Charming raconteurs, Jack, voluble in his nineties, and Ina, still prim in her eighties, speak mostly in English, sometimes switching to Dutch. Ohayon brings them back to Holland to trace their pre-war lives step-by-step under the restrictions during the German occupation. (Jack’s parents and in-laws insisted he put off divorce until after the war).

While they voice their regrets about their responsibilities towards others, his sister Betty seems Cassandra-like in describing how she and her husband went into hiding early and were rare Jewish participants in the Dutch Resistance. Her gutsiness before, during, and after the war, strikingly parallels elements in Paul Verhoeven’s Black Book, though these Jews are a lot more bitter about Dutch Queen Wilhelmina, who left the country for English exile. When Jack and Ina were finally free to marry in Amsterdam, they were two of only 5,400 of its 100,000 Jews who lived to return.

When the camera focuses intently on old photographs, Ohayon and her cinematographer, husband and co-producer Theo Van De Sande, go beyond Ken Burns’ techniques of adding sound effects (such as German actors voicing reenactments of Nazi orders), as the contemporary visuals of present-day locations blend into black-and-white film. The most amazing archival images are the extended excerpts from the 16mm reels of daily life at Westerbork that the Nazi commandant consented or commissioned to have filmed by inmate photographer Rudolf Breslauer. (Historians have different explanations for its purpose, but regardless, Breslauer was sent to his death at Auschwitz immediately upon its completion). It also includes the only extant footage of people being loaded into cattle cars to Auschwitz while Jack remembers assisting his parents on to such a train to the unknown. Jack and Ina’s chronicle of the everyday conditions at Bergen-Belsen is accompanied by previously unseen outtakes by British photographers at liberation. Ohayon also tracked down soldiers’ photographs of the exact trains that Ina was on at the end of the war when the couple was again separated.

Jack says that one of the proudest moments of his life was reading aloud the Declaration of Human Rights at a United Nations commemoration, and while he credits his and Ina’s survival to 97% luck, what also comes through from then and now, as they celebrate their 60th wedding anniversary in America, is his unquenchable optimism. My own neighborhood in Queens has been enriched by the many refugees and survivors from the Holocaust who, like the Polaks, have only gradually revealed their experiences to family and neighbors. Through articulate words, riveting images and a passionate story of the human spirit, Steal a Pencil for Me beautifully and cogently brings the immediacy of such eyewitness insights to a wider audience.