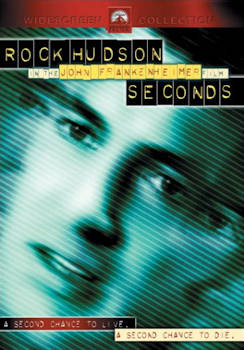

SECONDS

Released: 1966

Directed by: John Frankenheimer

(Based on a novel by David Ely)

Cast:

Rock Hudson: Tony Wilson

John Randolph: Arthur Hamilton

Salome Jens: Nora Marcus

SECONDSReleased: 1966

|

|

Review by Landon Palmer, FilmSchoolRejects.com

John Frankenheimer’s Seconds: The Loneliest Studio Film of the 1960s

It’s difficult to imagine what it must have been like to see Seconds in 1966. The third entry in John Frankenheimer’s unofficial “paranoia trilogy” (the other two titles being The Manchurian Candidate and Seven Days in May), this adaptation of David Ely’s novel of the same name saw the director shifting from political conspiracies to a full fledged existential crisis of masculine identity. The dystopian sci-fi/psychedelic noir is easily one of the darkest, loneliest films ever funded by a Hollywood studio.

That Seconds also stars Rock Hudson—the handsome, unassuming lead of many successful Technicolor comedies and a man rarely afforded the title of “serious actor” during his time—in a role originally meant for Laurence Olivier likely heightened the disorientation that made Seconds such an un-remarked-upon film (read: total flop) during its original release.

It’s not that Seconds is an anachronism. The case is very much the opposite—the film lies squarely at the intersection of post-McCarthyist paranoia, revisited themes of ’60s European art cinema, The Twilight Zone, and at the same time largely predicted the crises of masculinity and nightmarish interpretations of the counterculture to come in Hollywood cinema of the late ’60s and throughout the ’70s. Sure, Seconds may have been more adequately recognized during its time had it been released somewhere between The Parallax View and Taxi Driver, but there’s something perfect about its uncanny timeliness, its perverse use of a squeaky-clean movie star, and the layers of meaning that become ever more clear with its age.

And now it’s in The Criterion Collection.

Seconds Then

As remarked upon by R. Barton Palmer (no relation) and Murray Pomerance in their visual essay accompanying the Criterion disc, Seconds upon release had more in common with European art cinema than mid-60s Hollywood filmmaking in terms of both its themes and its visual style.

The film is an Albert Camus-meets-Philip K. Dick tale of an aging upper-middle class man despondent with life, with sex, with work, who finds an opportunity to start again with an organization that can stage his death and reconstruct his body as a younger, more handsome man (and in comes Rock Hudson). It’s a tale of masculine crisis (which became routine in 70s Hollywood and is now, arguably, the standard trope of “quality television”) by way of Sartre that was already well-evident in the films of Fellini and Bergman that packed metropolitan U.S. arthouses, but found distinct incompatibility with the proposed escapism of an increasingly weak studio system. That Hiroshi Teshigara’s The Face of Another was released the same year is as uncanny as it is instructive.

But it’s not only Seconds’s tale of male crisis that resonates with Cannes-friendly fare of the ’60s—Salome Jens’s Nora (Hudson’s “Tony Wilson’s” proposed means of escape from suburban banality) is a self-assured, liberated, modern counterpart that also contains substantial mystery. She’s no Felliniesque Madonna-or-whore counterpart to Wilson’s Guido, but stands alongside the strong, serious, complex women played by Liv Ullman and Monica Vitti. Her blonde hair blowing in the wind on an East Coast beach is directly reminiscent of L’Aventurra; she is both compelling and inaccessible, a magnetic but unsolvable enigma. (It’s worth noting that Antonioni’s far more objectifying Blow Up was also released the same year as Seconds.)

Beyond characterization, Seconds further resembles European art cinema in terms of its style. The film opens with Saul Bass’s Helvetica-perfect titles accompanying what looks like unanaesthetized surgery from the perspective of a fish-eyed knife, a horrifying cocktail of disembodied body parts in uber-close-up, all silently, helplessly receiving whatever dire fate this may be.

James Wong Howe’s wide-angle (and Oscar-nominated) cinematography does not slow its dynamism after this Vertigo-meets-David Lynch opening, seemingly caught in the subjectivity of its transformed protagonist—and all his worry, confusion, horror, and crippling insecurity—for the entire runtime. The film’s opening steadycam roam through Grand Central Station is as disorienting as anything for an institution supposedly still espousing the 180-degree rule, and David Newhouse’s editing readily embraces the breaks in continuity celebrated by the French New Wave.

Returning to my opening thought, I wonder how Seconds must have been seen by everyday audiences in 1966. Sure, American cinephiles may have seen stranger things by this point (and Frankenheimer’s early work certainly has its stylistic flourishes), but simply spending the first half hour of a “Rock Hudson movie” with blacklisted TV character actor John Randolph as the lead character (as Arthur Hamilton, who transforms into Hudson’s Wilson) doing his very best to perform quiet, slowly devastating despair, must have at least made audiences wonder, “Am I in the wrong theater?” It’s a disorientation that productively mirrors the fluid mystery of Seconds’s narrative. Never has a movie about a topic so inherently liberating—the literal change of identity—felt so claustrophobic.

Seconds Now

One of the most shocking, un-Hollywood things about Seconds is its portrayal of love. As observed by Palmer and Pomerance, the kiss shared between Hamilton and his wife toward the film’s opening is portrayed in an extreme close-up with high key lighting, staging the kiss as the grotesque meeting between two bodies of flesh—a grim portrayal of a totally dispassionate display of affection if there ever were one. Nora, who seems at first to be the film’s requisite platinum blonde, is staged as the first opportunity for Wilson’s happily-ever-after true love and his relief from everyday pain, but she instead diverts herself from being an object of male consumption and transforms into an agent far more complex and mysterious than a femme fatale or leading lady.

Seconds is a film about the fiction of the supposed sites of relief in an America that faced the very real threat of total annihilation; neither domestic contentment or countercultural polyamorous carnivalism can fulfill the void of the self. Perhaps the film’s most starkly honest moment is Wilson’s visit to Hamilton’s wife, who thinks (understandably) her husband is dead instead of sitting right before her in another body. Thus, Hamilton/Wilson hears for the first time his wife’s honest thoughts of their marriage—the years of silent distance, the inability to read one another, the slow change into somebody totally unrecognizable in front of the person you ostensibly share your life with. It’s in this regard that Seconds uses science fiction’s greatest tool: the potential for implausible scenarios to materialize profound truths that don’t embrace typically narrative exploration in a more straightforward way.

At its most desperate, threatened moment, the postwar American culture depicted in Frankenheimer’s paranoia films wouldn’t divest the strict “virtues” of “being normal.” Sure, Seconds wasn’t totally alone in this regard. The film that beat Seconds for Best Cinematography, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, put “happily ever after” and the Hays Code to rest by staging the era’s biggest stars in a verbal (and physical) boxing match. But in Seconds, Hudson doesn’t have a partner with which he can compete in his despair.

Hudson’s performance was maligned by critics during Seconds’s original release, as critics saw Hudson attempting to fill dramatic boots far too big for him. But that’s exactly what makes Hudson’s role here (even more so in retrospect) come across so powerfully.

It’s difficult not to read the gap between Hudson’s own private and public life into his character in Seconds. For the inebriated party scene in which Wilson reveals himself as a “second” to his swinging new neighbors, Frankenheimer (according to Alec Baldwin in another of Criterion’s special features) got Hudson plastered in order to effectively stage his move from bumbling host to total meltdown. Wilson attempts to divulge the truth to his neighbors, but he is quickly reprimanded for breaking decorum, for not playing his role amongst his hand-picked corporate friends staging his alternative life. Even in a supposedly liberated community, there is no room for deviating from convention. So go mid-’60s Hollywood cocktail parties, I assume.

Seconds is a film both profoundly of its time and insightful enough to see beyond it.