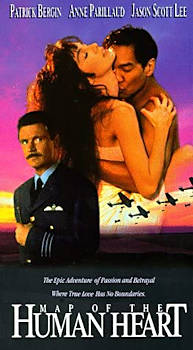

MAP OF THE HUMAN HEART

Released: 1993

Directed by: Vincent Ward

Cast:

Jason Scott Lee: Avik

Anne Parillaud: Albertine

Patrick Bergin: Walter Russell

John Cusack: The Mapmaker

Jeanne Moreau: Sister Banville

MAP OF THE HUMAN HEARTReleased: 1993

|

|

Review by Hal Hinson, The Washington Post

New Zealand-born filmmaker Vincent Ward is a true romantic. In everything he attempts he leads with his heart, which expresses itself lavishly (though somewhat mournfully) in passionate extravagance. This perplexed but vital organ is the engine of his visions, which with each new film grow larger, stronger, more personal and more boldly poetic.

With his most recent and most astounding film, Map of the Human Heart, Ward has climbed not one but several rungs up the ladder of his talents. This movie announces itself with symphonic authority. If Ward is a dreamer, he is not the spindly, alienated modern sort. Ward is out there poking around in the mythic stew, hooked into the ancestral line of shaman-storytellers, who repeated their dreams around campfires. Even though the script was written by Louis Nowra, the story belongs completely to Ward. His sensibility infuses everything, the characters, the sprawling landscapes, even the weather. Like most romantics, he’s not a great thinker, and, at times, his ideas about the world are almost simplistic and naïve. But the sheer audacity of his imagemaking reduces any intellectual quibbles to insignificance. Ward doesn’t pretend to be a primitive, but he does seem to have access within himself to the same wellspring of inspiration.

The story is not easy to synopsize. Our narrator is a half-Eskimo named Avik (Jason Scott Lee), who, when the film begins at the Arctic Circle in 1965, is a pathetic drunk telling the story of his life to a young mapmaker (John Cusack). Certainly the whopping, globe-trotting yarn that Avik unspools, helping himself at intervals to the whiskey bottle at the cartographer’s elbow, is a challenge to any thinking person’s sense of the probable.

Promptly, our narrator shifts back in time to the Arctic Circle in 1921 and the arrival of an earlier mapmaker’s airplane. Because neither Avik—who is then a young boy (played stunningly by Robert Joamie)—nor any of the other Inuits has seen either a white man or an airplane, the magical appearance of this swaggering Englishman (Patrick Bergen) causes quite a stir. At first the Eskimos aren’t sure if he’s a man or god or an evil spirit sent to punish them. And, in a sense, Walter is all three. After descending from the skies, Walter discovers that Avik has tuberculosis and whisks him off to a sanitarium in Montreal for a dose of “white man’s medicine.”

In these jolting, hypnotic opening scenes, Ward presents Avik’s strange new white man’s world as an alien planet; at first, everything is so peculiar that Avik fears he might have died and gone to Heaven. At this stage, it looks as though Ward would like to portray Avik as a kind of Wild Child in his natural, unpolluted state. And the scenes in the sanitarium are designed to show how, gradually, he is westernized and forced to turn away from his true self. The turning point in Avik’s life comes when he meets a beautiful half-Indian girl named Albertine (Annie Galipeau), who plays the role of soul mate until she is persuaded to pull away from him by one of the Catholic sisters running the sanitarium (Jeanne Moreau) because, though she can pass for white, he can’t. As long as she is with Avik, she will never have a future; without him, she is told, “anything is possible.”

Abruptly, Ward moves forward nearly 10 years—when, for a second time, Walter descends on Avik’s village, finding his old friend in bad shape. Since Avik’s earlier return to his people, he says, the goddess of the hunt has cursed his tribe. His people are starving, and because he was “poisoned” by the white man, they blame him for their misfortune. Though Walter offers Avik a lift back to the modern world, the boy—now 21—chooses to stay behind with his ailing grandmother. Before Walter takes off for Montreal, though, Avik gives him an x-ray of Albertine that he’d been carrying around, urging him to look her up and tell her he still loves her.

Walter looks her up, all right, but when he does, he claims Albertine—now grown up (and played by Anne Parillaud)—for himself. Meanwhile, Avik’s tribe moves on without him, and Avik joins the British air force as a bombardier. He once again runs into Albertine and renews their romance. Ward plays the star-crossed love affair between Avik and Albertine as a primal connection. Though Albertine is ambitious and wants more out of life than Avik can offer her, she also knows that she is linked to him forever on some essential level that Walter can never rival.

Not many filmmakers would attempt to interrupt the course of a love affair with the fire-bombing of Dresden, but Ward plunges in where angels—perhaps rightly so—fear to tread. The shots of Avik in his airplane over the bomb-lit German sky, though, are stunning, as is most of what Ward puts up on screen. As he did in Vigil and The Navigator, Ward communicates through big poetic connections, bridging the gap between epiphanies with striking visual motifs and metaphors—like the x-rays and the theme of flying—to carry the audience through the rough spots in the narrative. The movie is ravishingly bold, with the expansiveness and sweep of an epic, where both the players and their stage are larger than life, but without the loss in intimacy and specificity that usually accompanies grandly scaled visions.

As a final, wrongheaded twist, Ward dangles the possibility that Avik may be inventing this unbelievable story, merely to stay warm and within arm’s reach of the whiskey. And if only he had stopped there, with the audience still uncertain as to whether our hero is telling the truth. Still, even if the ending is sentimental and pat, Map of the Human Heart is a marvelous breakthrough, a film of incantatory intensity and moment by a prodigiously gifted young filmmaker.