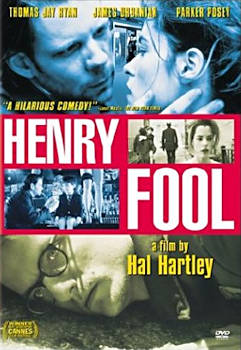

HENRY FOOL

Released: 1998

Written & Directed by: Hal Hartley

Cast:

Thomas Jay Ryan: Henry Fool

James Urbaniak: Simon Grim

Parker Posey: Fay Grim

Maria Porter: Mary Grim

HENRY FOOLReleased: 1998

|

|

Review by Janet Maslin, The New York Times

A PERFECT MODERN PARABLE

The affectless precision of Hal Hartley’s previous work is absolutely no preparation for the brilliance and deep resonance of his Henry Fool. Here is a great American film that’s no more likely than Nashville to turn up on the American Film Institute’s Top-100 hit parade (where Rocky outranks The Searchers) but will linger where it matters: in the hearts and minds of viewers receptive to its epic vision.

Without forsaking the clean, spare look and hyperreal clarity that are so much his own, Hartley moves into a much larger realm than was used in his earlier works. This film aspires to be a meditation on (among other things) art, trust, loyalty, politics and popular culture. With utter simplicity, and with unexpectedly intense storytelling, it achieves all that and more.

Shot so beautifully by Michael Spiller that its squalid Queens, N.Y., settings assume an instant mythic quality, Henry Fool is a perfect modern parable. It begins with the utter degradation of Simon Grim (James Urbaniak) and the mysterious appearance of a stranger who may be his salvation.

“Get up off your knees!” orders Henry Fool (Thomas Jay Ryan, a stage actor making a swaggeringly good screen debut) barging into the basement apartment in Henry’s house and instantly taking up residence. Henry’s arrival would be Faustian even if it were not, thanks to the basement hearth, greeted by a fiery glow.

The scarecrow-thin, owlish Simon (the haunting Urbaniak bears a deliberate resemblance here to young Samuel Beckett) works as a garbage man and takes heaps of abuse from much of the neighborhood. That includes his heavily medicated mother (Maria Porter) and his slatternly sister Fay (played with deadpan, nonchalant wit by Parker Posey, in one of her best roles). Simon is so silent that his response to this literally and figuratively Grim existence is a mystery until Henry urges him to write down his thoughts.

Henry describes his own huge, unpublished work, known variously as “my opus” or “my confession,” with supreme grandiosity. “It’s a philosophy,” he tells Simon. “A poetics. A politics, if you will. A literature of protest. A novel of ideas. A pornographic magazine of truly comic-book proportions.” The work’s mystique comes from Henry’s cagey unwillingness to let anyone see it.

Simon’s writing also remains hidden at first (and always wisely hidden from the audience). But as it starts to emerge, its effects are astonishing. The mute girl at the local World of Donuts, this story’s cultural and culinary mecca, reads a few words and she suddenly sings. A girl who once bullied him becomes a literary groupie in a beret. A waitress with conservative political leanings is offended. “You brought on my period a week and a half early, so just shut up!” complains Fay, after typing Simon’s manuscript. When the Board of Education denounces Simon’s poem as scatological (in a film that insists on a few wild gross-outs of its own), Simon and Henry share a proud handshake. “An honest man is always in trouble,” Henry has announced early in the story, and an honest artist is, too.

Genius and celebrity eventually shift the story’s balance in wry ways. There’s an especially droll sequence devoted to the world of publishing, where slick young executives insist on thinking way beyond mere books. The effect of a right-wing political candidate on the neighborhood’s sleaziest character (Kevin Corrigan) points to another wave of the future. But the tension between Simon’s utter seriousness and Henry’s big dreams always remains the story’s central concern, especially after Simon learns more about Henry’s past. “To be honest, my ideas, my writing, they’ve not always been received well—or even calmly,” Henry eventually confesses.

Henry Fool is its own testament to the power of words, even as it merges the fortunes of its characters in a wonderfully ambiguous final gesture. Hartley’s splendidly articulate screenplay (which won a prize at Cannes this year) is as exacting as his visual style. Even more than its story of private genius and public opinion, the dialogue itself offers proof that every word matters. All the film’s characters speak with utter honesty about matters both large and small, and sometimes make a major virtue of understatement. As in: “Look, Simon, I made love to your mother about half an hour ago, and I’m beginning to think it wasn’t such a good idea.”

Visually, Henry Fool shows off such fine compositional sense that there’s not a paint streak on a wall that doesn’t tie in with some other part of the frame. There are no casual details and absolutely no clutter. Props are where Hartley finds them, to the point where a stack of huge tires, a gum-ball machine or a garden hose can be as arresting as another film’s elaborate set. Everything the camera sees is present for a reason.