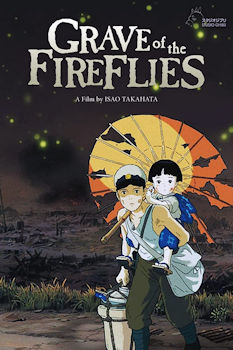

GRAVE OF THE FIREFLIES

(Hotaru no Haka)

Released: 1988

Directed By: Isao Takahata

Based on a novel by Akiyuki Nosaka

Japanese anime with English subtitles

and English dubbing

Cast (voices):

Tustomu Tatsumi: Seita

Ayano Shiraishi: Setsuko

Akemi Yamaguchi: Aunt

|

|

Film critic Dennis Fukushima, citing an interview with Akiyuki Nosaka, author of the novel that Grave of the Fireflies is based on:

Having been the sole survivor, he felt guilty for the death of his sister. While scrounging for food, he had often fed himself first, and his sister second. Her undeniable cause of death was hunger, and it was a sad fact that would haunt Nosaka for years. It prompted him to write about the experience, in hopes of purging the demons tormenting him.

Review by Ernest Rister

The legend goes that no one had ever been moved to tears by an animated work until the night of December 21, 1937 and the world premiere of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. The Disney animators themselves were reportedly shocked when—as Snow White lay in her bier—sniffles and then real sobs began to sound throughout the auditorium. “We couldn’t believe it. This was just a cartoon,” Disney animator Ward Kimball would later say, “Everybody was crying.” Daily Variety, in reviewing the film the following morning, had to repeat itself, exclaiming, “tears—yes, tears” in trying to accurately convey the emotion of Snow White’s premiere.

It was an impressive breakthrough—for the first time, animated characters had been given the space and the time to develop into fully realized personalities, and the future of animation looked extraordinarily bright. To this day, animation enthusiasts speculate where Walt would have taken animation if the marketplace for costly flops like Fantasia and Pinocchio had been different. While some ascribe the blame of decades of sugar-coated animated children’s fare to Walt Disney, this notion is uninformed and incorrect. Walt wanted animated films to be given respect by his peers, and he and his artists struggled to make their films as dramatically powerful as any live action film could ever be.

Plaguing Walt was the notion that his medium was irrevocably distancing to people because of its inherent unreality. Animated characters aren’t real, and your rational mind knows this. This built-in feature of animation as an unreal interpretation of life—as opposed to a re-creation of life—quickly developed into the medium’s biggest strength, impacting children and adults on more levels than anyone had first suspected.

Consider that unreal image of the young fawn in Bambi. Your rational mind knows that image of a cartoon deer is not a real deer. It knows the image “stands for” a deer, and once your mind starts down that path, all sorts of associations can follow with it, making the image that much more vivid, particularly to young minds, I believe. The cartoon deer might wind up representing—on a very deep level—anything your subconscious attaches to it. Snow White may rankle the older audience member because they associate her with outmoded female roles, but a child only sees her as a character first, then—deeper down—as a Mother figure, caring for little guys about their own height. And they see the Queen, of course, as Death. It’s no accident she morphs into an extremely aged figure when she comes to kill her stepchild.

In this associative way, animated characters are moving ideas, arguing for or against the main theme of the material. And in this way, animation can—at times—touch us more deeply than any number of live-action dramas, accomplishing Walt’s goal. Which brings us, of course, to Grave of the Fireflies.

Fifty years after that momentous premiere of Snow White, the small Japanese animated film Grave of the Fireflies made its way across the pond to America, where it met great resistance in trying to find distribution. The film was quickly dismissed and relegated to the back anime shelves of your local Blockbuster. Although championed by a few well-known film critics, most notably Roger Ebert, the film was in direct conflict with the attitudes towards animation still dominant in American society. Telling the tale of two Japanese children who suffer mightily from the indifference of those around them during the closing moments of World War II—and telling it in an adult way—Fireflies was a long way from the mood of the country, which was at that time rewarding some of the worst animated features ever made with decent box office returns (specifically, Oliver and Co. and the hordes of low-budget products like Rainbow Brite and the Star Stealers and Care Bears in Wonderland). Like Fantasia decades earlier, America simply wasn’t ready for it.

Fireflies is a Japanese anime film with the usual limited animation, running headlong against Character Animation dogma which argues for believability through caricature of movement. And yet, of any animated film I have ever seen that deals with human beings, despite the “unrealistic” limited animation, despite the anime stylizations, Fireflies is the most profoundly human animated film I’ve ever seen. This is to animation what Schindler’s List was to Steven Spielberg—both a long overdue display of artistic maturity and a bold statement of ability.

The film was written and directed by Isao Takahata, and remains my first and only exposure to his work as an animation director, a career which stretches, I am told, some thirty years. His main strength as the storyteller of Fireflies is his control and authority. I’m particularly impressed with his use of long extended shots of his characters as they move about (or ponder) their environs. American animated films are terrified of shots that last more than 5-7 seconds, because they’re harder, require extensive planning, and task the animator’s talent considerably. And they cost more. Animated films are usually highly efficient narrative machines, with no time or money wasted on the kind of emotional reality or lyricism Takahata revels in.

Fireflies is aggressive in its use of extended shots, and it allows Takahata’s animators to breathe wonderfully seen behaviors into their characters. There’s a moment where the boy Seita traps an air bubble with a wash rag, submerges it, and then releases it into his sister Setsuko’s delighted face—and that’s when I knew I was watching something special. Details of behavior like that and an extended shot of a saddened Setsuko slowly swaying back and forth give the film a heightened naturalism, accomplishing Disney’s goal of believability through a back door approach. Takahata’s animation doesn’t fool your eye, but his intelligence and observations fool your brain. Just as we come to believe that the cartoon deer is real because it moves in a realistic way, we come to believe these children are real—not because they move realistically, because they don’t—but because they behave realistically. That ONLY comes from an animator’s observation and talent. These ARE real children, we come to believe, and we mourn for them—we become deeply involved in the plight of these two small moving ideas.

Fireflies is dependent on all of its details for its effect, especially the more gruesome ones, and the film pulls no punches—the FX Animation in particular is so detailed you can almost feel the hot air sweeping the cinders down the burning Kobe streets. But Takahata doesn’t employ shots of charred flesh for shock value—they’re played “real”, the characters and the camera lingering on such images in grief and horror before turning away in denial. By the end of the film, the camera cannot turn away any longer and the extended final moments with these characters are given their full measure of worth and heartbreak. It is a devastating experience.

Disney never intended for animation to become a medium for children in America; in fact, he once grew angry when a storyman referred to Fantasia as a cartoon. Fireflies is so important to me personally for a number of reasons—primarily because it unleashes the full undiluted power of the medium onto a mature modern story without the slightest pretext of pandering to seven year olds. Compare Fireflies’ control and emotional intelligence to Disney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame, one of my favorite animated films, and yet I’ll be the first one to tell you its a film emasculated by concerns over the “squirm-factor” of toddlers. It’s always been my belief that if you can’t do Hunchback without pandering to the kids and destroying the tone and reality of the film, maybe you shouldn’t do Hunchback (the low comedy injected into deeply-felt moments like Quasimodo’s “Heaven’s Light” is unforgivable).

The only animated works I’ve seen that even approach both the heartbreak and the power of Fireflies are Disney’s Education for Death, the 1942 short now banned by the Disney Co. because of its subject matter—German children being brainwashed into the Hitler Youth—and Martin Rosen’s adaptation of Richard Adams’ The Plague Dogs. Both films are propaganda works, one against the evils of Fascism, the other against scientific animal experimentation.

But Fireflies is important, I think, because it isn’t a propaganda work. As an American, before viewing Fireflies, I assumed there would be a propaganda bent on at least some level. I knew it was about two Japanese children trying to survive the end of World War II, and that usually connotes at least one shot of an A-bomb. Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun is also about a child trying to survive World War II, but Steven’s film is set in mainland China and even he couldn’t resist sneaking in a flash of light that Jim imagines is the atomic blast at Hiroshima.

This never happens in Fireflies. The film isn’t concerned with such things, and in fact, patriotism and jingoism are concepts made moot by the material. The film is ultimately about our responsibility to one another as members of a human society, particularly a society being torn apart at the seams. The behaviors on display by the supporting characters, particularly Seita’s aunt, and the farmer who beats Seita severely, and even the doctor who treats the scurvy-ravaged Setsuko—they are all models of self-involvement in the face of a deep humanitarian need. As a matter of fact, it is America that gets off rather lightly, with no mention of either Atomic blast, nor criticism of the “total war” approach on the civilian populace, while the inhumanity of humans in a crumbling society is brought to the fore. It is not a propaganda work—it is a universal one. Fundamental decency doesn’t belong to a race, or a government.

It is a shattering experience.

Review by Elle Chapman, WSWS.org

Grave of the Fireflies (Hotaru No Haka) is a remarkable animation feature about two orphaned children during the U.S. firebombing of Japanese cities in World War II. The movie was screened at this year’s Sydney Film Festival—one of the rare occasions that it has been shown in an Australian cinema since its Japan release more than 25 years ago.

Directed by Isao Takahata and produced by Studio Ghibli, the 89-minute movie centers on the relationship between a teenage boy, Seita, and his four-year-old sister, Setsuko. The resourceful boy and the tenderness of his relationship with his sister allow the pair to endure, for a time, the hardship and horrors produced by the US firebombing campaign, one of the lesser-known war crimes of WWII.

Fireflies does not provide viewers with a detailed examination of the U.S. bombing campaign—Japanese knowledge of the war horrors was well-known when the movie was made in 1987—and so some details about the brutal U.S. operation are required here.

The firebombing campaign was initiated under U.S. General Curtis LeMay in 1945, a few months before the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the final Japanese surrender. The operation began in early March with hundreds of B-29s dropping tons of napalm, phosphorus and other incendiary bombs on scores of cities. These were aimed at sparking massive firestorms that the inadequate Japanese emergency services were incapable of fighting, destroying the country’s urban infrastructure and maximising civilian casualties. “Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at that time,” U.S.A.F. commander LeMay later chillingly admitted, but “I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal.”

LeMay’s campaign lasted five months, devastating more than 60 Japanese cities, killing an estimated 500,000 civilians, injuring 400,000 and rendering five million homeless.

In Tokyo over 100,000 residents died and 260,000 buildings were incinerated in six hours. One survivor described the streets as “rivers of fire” with wooden homes, furniture and people “exploding in the heat” and “immense incandescent vortices...swirling, flattening, sucking whole blocks of houses into their maelstrom of fire.”

Kobe was bombed a few days later with almost half the city—a manufacturing, business and transport hub—totally destroyed. Eight thousand were killed and 650,000 of the city’s one million inhabitants rendered homeless. Fireflies, which is set in Kobe, is based on the semi-autobiographical novel of the same name by Akiyuki Nosaka, one of the thousands of Japanese children whose parents were killed in the bombings.

The movie begins on September 21, 1945, just after the Japanese surrender. The emaciated Seita is found dead in Kobe’s Sannomiya Station by a railway cleaner. The story then flashes back to the firebombing raid on Kobe, where the young boy is preparing to flee with his sister Setsuko to an air raid shelter. In a brief tender moment—one of many throughout the film—the boy ensures that his young sister is safely secured to his back and then stoops to pick up her doll which is almost forgotten in the rush.

The two children survive the bombing and subsequent inferno but many around them die of horrific burns and the city is devastated. We later learn that their mother—who failed to make it to a bomb shelter—is badly burned and eventually dies. She is shown tightly wrapped from head to foot in bloody bandages with only her closed eyes and charred lips visible.

With their mother dead and their father serving in the navy—uncontactable, presumed dead—the children are forced to rely on the charity of a distant but harsh aunt. The aunt persuades Seita to sell his mother’s kimonos in order to buy food and when that is consumed she becomes increasingly spiteful towards the children.

Seita tries to shield his sister from the woman, shows her how to catch fireflies, which delights the little girl, takes her to the beach to swim and play, and gives her fruit candy drops to cheer her up and ease her hunger pains. Eventually they find it impossible to continue living with their aunt and make a new home for themselves in a disused tunnel near a river. It is here that the film’s title is borne out.

One morning after the siblings have caught many fireflies and marvelled at their twinkling lights, Seita discovers Setsuko burying the insects that have perished overnight. The little girl has made a connection between the dead fireflies and their mother, and Seita is overcome with emotion. The fireflies, in fact, becomes a complex visual and emotional symbol for the children—of the firebombing itself, which they do not talk about, but also of life, intimacy, of spirit and of the sibling’s close bonds.

When it was originally released Fireflies represented an important departure from the subject of animated films that usually focused on escapist fantasies or science fiction stories. The genre was rarely, if ever, used to openly explore social themes. Director Isao Takahata, however, had been influenced by post-WWII Italian neo-realist movies and their examination of the lives and struggles of working people or those living on society’s margins.

In contrast to the black-and-white semi-documentary approach of the neo-realists, Takahata’s film has a quiet, nuanced quality and its visual lines are delicate with the children’s faces soft and expressive.

Many of the scenes, particularly those in which Setsuko and Seita survey the bombed out ruins of their city, have a painterly, almost watercolor appearance. These are counterposed against the gentle light of the fireflies and the bird sounds at the children’s riverside temporary tunnel home. Takahata often lingers on the rural scenes for extended periods, giving the viewer time for reflection.

Fireflies is an engrossing and convincing work. The children experience the death of a family member, starvation, homelessness and other catastrophes produced by the war, but throughout these ordeals Seita remains absolutely devoted to his sister and infused with an instinctive belief that they have the right to live a happy and normal life.

Many Western film critics have rightly praised Fireflies as an important exposure of the horrors of war with several hailing it as a powerful anti-war movie. These critiques, however, have been rejected by Takahata and the novelist Akiyuki Nosaka who insisted that the work has no political content.

Nosaka, whose sister died of starvation and whose adoptive father was killed in the Kobe bombing raids, has said that his novel was written to assuage the deep sense of guilt he felt about her passing. The film, Takahata told one interviewer, “is not at all an anti-war anime and contains absolutely no such message.”

Notwithstanding these denials, Fireflies speaks for itself and like the best work of the Italian neo-realists sensitively explores how World War II impacted children, the most vulnerable members of society. The movie is a valuable antidote to the scores of action-packed glorifications of militarism and war dominating cinemas and television and should be watched by adults and children alike. It is widely available on DVD and Blu-ray in multi-language subtitle or dubbed versions.