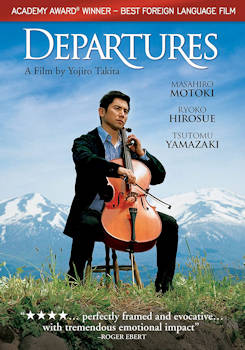

DEPARTURES

(OKURIBITO)

Released: 2008

Directed By: Yojiro Takita

Japanese with English subtitles

Cast:

Masahiro Motoki: Daigo Kobayashi

Ryoko Hisosue: Mika Kobayashi

Tsutomu Yamazaki: Sasaki

Tetta Sugimoto: Yamashita

DEPARTURES

|

|

Review by Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat, SpiritualityAndPractice.com

Daigo Kobayashi (Masahiro Motoki) has been playing the cello since childhood and has a job with a symphony orchestra in Tokyo. He is shattered when it is disbanded. He reluctantly admits to his wife, Mika (Ryoko Hisosue), that he has gone deep in debt to purchase his cello. With no other position in sight, he sells the instrument and moves back to his hometown to live in the house his recently deceased mother left to him. Mika cheerfully goes along with this major change in their lives. She is intrigued by the stories the house contains. Why, for example, did Daigo’s mother keep his father’s records after he walked out on the family when Daigo was only six years old? This abandonment has deeply troubled him in adulthood.

Looking for a new career, Daigo answers an ad to work in “Departures,” thinking it is part of the travel industry. But when he arrives at the office he learns that the ad has a misprint; it should have said working with “the departed.” The company owner, Sasaki (Tsutomu Yamazaki), a no-nonsense man of few words, is a master artist of “encoffination”—the ceremonial washing, dressing, and placing of the deceased into a coffin in the presence of the bereaved.

Although he is shocked by what he thinks must be the grim nature of the work, Daigo agrees to give it a try and accompanies Sasaki to a theater where a film crew is preparing a training video; he is to be the corpse his new boss works on. His next assignment is even more difficult. They must casket the body of a woman who has been dead in her house for several days.

Daigo is ashamed of his new job and keeps it a secret from Mika, fearing that she might react poorly to it. When Yamashita (Tetta Sugimoto), one of his friends since childhood, finds out what he does, he shuns him because of the stigma attached to undertakers. Eventually, Mika sees the training tape and demands that Daigo resign because she finds him to be unclean. She wants him to get a “normal” job, but he replies that “Death is normal.” She leaves and returns to her family in Tokyo.

Daigo starts to play the cello again, the one he had as a child. During the Christmas holidays, he plays “Ave Maria” for Sasaki and his secretary (Kimiko Yo), and they are impressed with his talent. They are already happy with the way he has taken to his work, and he is now doing ceremonies on his own. In three different rituals, Daigo realizes that he is creating beautiful music in these new settings. In one ceremony, he allows family members to put children’s white socks on their deceased grandmother; in another, he is surprised while washing a female suicide victim; and, in the most touching of all, he deals with his own feelings of grief when called upon to prepare the body of Yamashita’s mother, who ran a local bath house and played an influential role in Daigo’s childhood.

Departures received the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film of 2008. Japanese director Yojiro Takita has created a cinematic masterpiece that is both funny and sad and all the emotions in between. It touches the heart as it depicts the slow process through which a young man comes to terms with his destiny and the abandonment by his father that he still feels. When it is time for him to reach out to Mika, he recalls that his father once gave him a “stone letter.” Presenting his wife with a small rock, he explains: “Long ago, before writing, you’d send someone a stone that suited how you were feeling. From its weight and touch, they’d know how you felt. From a smooth stone, they might get that you were happy. Or from a rough one that you were worried about them.” This is just one moment in the film that conveys the deep symbolic value of ritual. And there are many more!

The story revolves around scenes of the encoffination ceremony, described early on as “preparing the deceased for a peaceful departure.” At first frightened by death, Daigo comes to see how his work helps the family and friends of the deceased access and express their grief. He brings dignity and beauty to these intimate moments. Every gesture in the ritual washing, dressing, grooming, and putting on of make-up is performed with the kind of presence and attention we would associate with the Japanese tea ceremony. Not a movement is wasted in this art which moves slowly and demonstrates that touch is the most exquisite of our senses.

English novelist and poet D. H. Lawrence once observed: “The human soul needs beauty even more than it needs bread.” When we left this film, we exclaimed, “It is just so beautiful!” Here are just a few examples:

• the Tokyo symphony orchestra performing Beethoven’s Ninth symphony;

• Miko’s cheerfulness as she greets her husband;

• the exquisite attention to detail and reverence for the deceased demonstrated by Sasaki;

• the melodic and flowing cello playing by Daigo;

• a scene in which Daigo stares at the salmon swimming upstream to lay their eggs as a dead salmon floats downstream;

• the bowing to greet people and the deep bows at the end of the ceremonies;

• Sasaki’s enthusiasm for a good meal;

• the changing expressions on Yamashita’s face as he watches the casketing of his mother;

• the attitude of Shokichi Hirata (Takashi Sasano), a frequent visitor to the bathhouse, toward his work at the crematorium;

• Miko’s growing understanding of and pride in what her husband does;

• Daigo’s keen awareness of just what is needed to help someone—including himself—grieve.