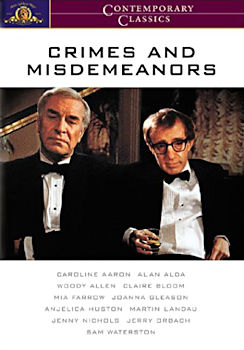

CRIMES AND MISDEMEANORS

Released: 1989

Written & Directed by: Woody Allen

Cast:

Martin Landau: Judah Rosenthal

Woody Allen: Cliff Stern

Anjelica Huston: Dolores Paley

Mia Farrow: Halley Reed

Alan Alda: Lester

Sam Waterston: Ben

CRIMES AND MISDEMEANORSReleased: 1989

|

|

Review by Roger Ebert, the Chicago Sun-Times

Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors is a thriller about the dark nights of the soul. It shockingly answers the question most of us have asked ourselves from time to time: Could I live with the knowledge that I had murdered someone? Could I still get through the day and be close to my family and warm to my friends knowing that because of my own cruel selfishness, someone who had loved me was lying dead in the grave?

This is one of the central questions of human existence, and society is based on the fact that most of us are not willing to see ourselves as murderers. But in the world of this Woody Allen film, conventional piety is overturned, and we see into the soul of a human monster. Actually, he seems like a pretty nice guy. He’s an eye doctor with a thriving practice, he lives in a modern home on three acres in Connecticut, he has a loving wife and nice kids and lots of friends, and then he has a mistress who is going crazy and threatening to start making phone calls and destroy everything. This will not do. He has built up a comfortable and well-regulated life over the years and is respected in the community. He can’t let some crazy woman bring a scandal crashing around his head.

Crimes and Misdemeanors tells his story with what Allen calls realism, and what others might call bleak irony. He also tells it with a great deal of humor. Who else but Woody Allen could make a movie in which virtue is punished, evildoing is rewarded, and there is a lot of laughter—even subversive laughter at the most shocking times?

Martin Landau stars in the film as the opthalmologist who has been faithful to his wife (Claire Bloom) for years—all except for a passionate recent affair with a flight attendant (Anjelica Huston). For a few blessed months he felt free and young again, and they walked on the beach, and he said things that sounded to her like plans for marriage. But he is incapable of leaving his wife, and when she finally realizes that she becomes enraged.

What can the doctor do? It’s a Fatal Attraction situation, and she’s sending letters to his wife (which he barely intercepts) and calling up from the gas station down the road threatening to come to his door and reveal everything. In desperation, the doctor turns to his brother (Jerry Orbach), who has Mafia connections. And the brother says that there’s really no problem, because he can make one telephone call and the problem will go away.

Are we talking... murder? The doctor can barely bring himself to say the word. But his brother is more realistic and certainly more honest, and soon the doctor is forced to ask, and answer, basic questions about his own values. Allen uses flashbacks to establish the childhood of both brothers, who grew up in a religious Jewish family with a father who solemnly promised them that God saw everything, and that, even if He didn’t, a good man could not live happily with an evil deed on his conscience.

The story of the doctor’s dilemma takes place at the center of a large cast of characters—the movie resembles Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters in the way all of the lives become tangled. Among the other important characters are Allen himself, as a serious documentary filmmaker whose wife’s brother (Alan Alda) is a shallow TV sitcom producer of great wealth and appalling vanity. Through his wife’s intervention, Allen gets a job making a documentary about the Alda character—and then both men make a pass at the bright, attractive production assistant (Mia Farrow). Which will she choose? The dedicated documentarian or the powerful millionaire?

Another important character is a rabbi (Sam Waterston), who is going blind. The eye doctor treats him and then turns to him for moral guidance, and the rabbi, who is a good man, tells him what we would expect to hear. But the rabbi’s blindness is a symbol for the dark undercurrent of Crimes and Misdemeanors, which seems to argue that God has abandoned men, and that we live here below on a darkling plain, lost in violence, selfishness, and moral confusion.

Crimes and Misdemeanors is not, properly speaking, a thriller, and yet it plays like one. In fact, it plays a little like those film noir classics of the 1940s, like Double Indemnity, in which a man thinks of himself as moral, but finds out otherwise. The movie generates the best kind of suspense, because it’s not about what will happen to people, it’s about what decisions they will reach. We have the same information they have. What would we do? How far would we go to protect our happiness and reputation? How selfish would we be? Is our comfort worth more than another person’s life? Woody Allen does not evade this question, and his answer seems to be, yes, for some people. Anyone who reads the crime reports in the daily papers would be hard put to disagree with him.