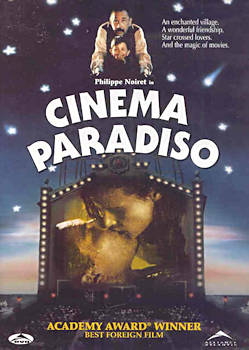

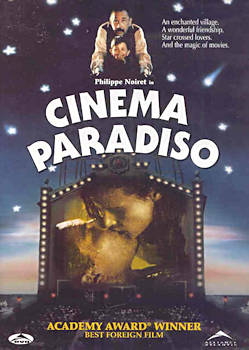

CINEMA PARADISO

Released: 1989

Written & Directed By: Giuseppe Tornatore

Italian with English subtitles

Cast:

Salvatore Cascio: Salvatore (Child)

Marco Leonardi: Salvatore (Adolescent)

Jacques Perrin: Salvatore (Adult)

Philippe Noiret: Alfredo

Agnese Nano: Elena (Adolescent)

Brigitte Fossey: Elena (Adult)

|

|

Review by James Berardinelli, Movie-reviews.Colossus.net

If you love movies, it’s impossible not to appreciate Cinema Paradiso, Giuseppe Tornatore’s heartwarming, nostalgic look at one man’s love affair with film, and the story of a very special friendship. Affecting (but not cloying) and sentimental (but not sappy), Cinema Paradiso is the kind of motion picture that can brighten up a gloomy day and bring a smile to the lips of the most taciturn individual. Light and romantic, this fantasy is tinged with just enough realism to make us believe in its magic, even as we are enraptured by its spell.

Most of Cinema Paradiso is told through flashbacks. As the film opens, we meet Salvatore (Jacques Perrin), a famous director, who has just received the news that an old friend has died. Before departing for his home village of Giancaldo the next morning to attend the funeral, he reminisces about his childhood and adolescence, thinking back to places and people he hasn’t seen for decades.

As a fatherless child, Salvatore (Salvatore Cascio) loved the movies. He would abscond with the milk money to buy admission to a matinee showing at the local theater, a small place called the Cinema Paradiso. Raised on an eclectic fare that included offerings from such diverse sources as Akira Kurosawa, Jean Renoir, John Wayne, and Charlie Chaplin, Salvatore grew to appreciate all kinds of film. The Paradiso became his home, and the movies, his parents. Eventually, he developed a friendship with the projectionist, Alfredo (Philippe Noiret), a lively middle-aged man who offered advice on life, romance, and how to run a movie theater. Salvatore worked as Alfredo’s unpaid apprentice until the day the Paradiso burned down. When a new cinema was erected on the same site, an adolescent Salvatore (Marco Leonardi) became the projectionist. But Alfredo, now blind because of injuries sustained in the fire, remained in the background, filling the role of confidante and mentor to the boy he loved like a son.

Cinema Paradiso’s first half, with Salvatore Cascio playing the young protagonist, is the superior portion. The boy’s experiences in the theater, watching movies and listening to Alfredo’s stories, form a kind of journey of discovery. As Salvatore cultivates his love of movies, those in the audience are prodded to recall the personal meaning of film. It’s an evocative and powerful experience that will touch lovers of motion pictures more deeply than it will casual movie-goers.

Once Salvatore has grown into his teens, Cinema Paradiso shifts from being a nostalgic celebration of movies to a traditional coming-of-age drama, complete with romantic disappointment and elation. Salvatore falls for a girl named Elena (Agnese Nano), but his deeply-felt passion isn’t reciprocated. So he agonizes over the situation, seeks out Alfredo’s advice, then makes a bold decision: he will stand outside of Elena’s window every night until she relents. In the end, love wins out, but Salvatore’s joy is eventually replaced by sadness as Elena vanishes forever from his life.

The Screen Kiss is important to Cinema Paradiso. Early in the film, the local priest previews each movie before it is available for public consumption, using the power of his office to demand that all scenes of kissing be edited out. By the time the new Paradiso opens, however, things have changed. The priest no longer goes to the movies and kisses aren’t censored. Much later, following the funeral near the end of Cinema Paradiso, Salvatore receives his bequest from Alfredo: a film reel containing all of the kisses removed from the movies shown at the Paradiso over the years. It’s perhaps the greatest montage of motion picture kisses ever assembled, and, as Salvatore watches it, tears come to his eyes. The deluge of concentrated ardor acts as a forceful reminder of the simple-yet-profound passion that has been absent from his life since he lost touch with his one true love, Elena. It’s a profoundly moving moment—one of many that Cinema Paradiso offers.

Is Cinema Paradiso manipulative? Manifestly so, but Tornatore displays such skill in the way he excites our emotions that we don’t care. This film is sometimes funny, sometimes joyful, and sometimes poignant, but it’s always warm, wonderful, and satisfying. Cinema Paradiso affects us on many levels, but its strongest connection is with our memories. We relate to Salvatore’s story not just because he’s a likable character, but because we relive our own childhood movie experiences through him. Who doesn’t remember the first time they sat in a theater, eagerly awaiting the lights to dim? There has always been a certain magic associated with the simple act of projecting a movie on a screen. Tornatore taps into this mystique, and that, more than anything else, is why Cinema Paradiso is a great motion picture.

Thoughts about the “Director’s Cut”:

When Cinema Paradiso was released in the late 1980s, the version seen by Italian movie-goers was much different than the cut shown to North American viewers. 51 minutes were sliced and diced from the U.S. release. The truncated edition is still a stunning, masterful production, but it leaves the audience with a nagging question: What really happened to Elena? The answer is provided in a 35-minute sequence that never made it into the 1988 American release, but which has now been restored.

Of the 51 “new” minutes of footage, most comes near the end, although several relatively inconsequential scenes have been re-inserted into the main story (one of which shows Salvatore losing his virginity). In the shorter version, Alfredo’s funeral functions as an epilogue. In the director’s cut, it’s a full third act that gives closure to Salvatore and Elena’s story and provides us with a more complete picture of Salvatore’s mentor. Rather than slowing down Cinema Paradiso’s pace, this footage enhances the film’s poignance and power, elevating it to a loftier level than the rarified one attained by the first cut. And, viewed after this new material, the Screen Kiss montage is even more touching and transcendant.

For lovers of Cinema Paradiso, widely regarded as one of the best foreign language films ever to grace American screens, this restored version is unquestionably a “must see”. The magic and poetry of the original remain, but the added scenes fashion a different, more complete cinematic experience. For those who have never seen Tornatore’s masterpiece, this is an excellent opportunity to view it for the first time.

Review by Glenn Erickson, DVDsavant.com

The foreign movie splash of 1990, Cinema Paradiso was a solid hit and award winner for Giuseppe Tornatore. Films that invoke the love of movies and the dreams they inspire often turn into mush, but Tornatore’s tale of the life of a ragtag tot who frequents a provincial Sicilian theater, and the romance of his life, manages to mix cinema, with the cinema in the cinema, and come out on top.

Slashed by a half hour for American audiences, Cinema Paradiso is one of many Miramax films still being regularly cut down upon import, a practice that few seem to notice in pictures such as Like Water for Chocolate (123 to 105 min.) and Amelie (129 to 122 min.). I at first thought this ‘special’ disc was Miramax’s way of giving us what we should have been given in the first place, but this is actually an extended cut 19 minutes longer than the original, and 51 minutes longer than the old American release. This new disc is a flipper; it also contains the old short cut for ready comparison.

Synopsis:

Although his mother (Antonella Attili) objects, tiny Salvatore (Salvatore Cascio) hangs out at the Cinema Paradiso, where projectionist Alfredo (Philippe Noiret) lets him play with the dangerous nitrate film clips, and watch while Father Aldelfio (Leopoldo Trieste) censors each new film before it screens, so as to be free of kisses, bare legs, and nudity. Unforseen events cause Salvatore to take Alfredo’s place as projectionist, and the changes in Italian cinema cruise by as he grows into manhood, frustrated by some things in his life, and enchanted by the love of his life, Elena (Agnese Nano).

Practically a multi-generational story on the order of an Edna Ferber epic, Cinema Paradiso uses a flashback format, for a fiftyish Salvatore, played by actor Jacques Perrin of Z fame, to reminisce about the magic of his youth and his bittersweet romance with Elena.

Director Tornatore uses his slightly-stylized techniques to lend a quality of magic realism to some scenes, such as the carved lion projector port that comes alive in one dramatic scene. We see many film clips projected on the Paradiso’s old screen, familiar Italian classics like La Terra Trema and Il Grido, and many (public domain) American titles—It’s a Wonderful Life, Stagecoach. Tornatore doesn’t play games with film history, and the titles help film fans keep the chronology of the movie straight. They also make mild comments on Salvatore’s situation: trapped in Giancaldo for the summer, he shows Ulysses, and we see the scene where they cyclops Polyphemus suffers in blind agony.

Tornatore definitely comes from the ‘glowing memory’ school of continental filmmaking, where the European past is seen in a nostalgic light, and picturesque locales are made to look gorgeous, better than they could possibly have been for real. Salvatore’s little stone town is a stunner, for sure.

Getting things off to a magical start are veteran Philipe Noiret (Thérèse Desqueyroux, Coup de Torchon, Il Postino) and young Salvatore Cascio, the cutest little boy ever in the movies. The mystery of life is seen through his eyes—the loss of his father in news delayed long after the war’s end, Alfredo’s accident, and the birth of a new Cinema Paradiso. Salvatore makes his own 16mm movies, and goes directly from recording the goings-on in a slaughterhouse, Franju-style, to using his camera to snatch precious images of the beautiful but unapproachable Elena, whom he worships from afar. Thankfully, there’s nothing Peeping Tom-ish about his intentions, but (spoiler) in the long run his patience does no good, and fate separates the pair. The romantic finales Salvatore wonders at in the movies don’t seem to work for him in real life.

In the shorter version we saw in 1990, the middle-aged Salvatore journeys to Giancaldo and sifts through the ashes of his earlier life, witnessing the dynamiting of the Paradiso to make way for a parking lot. Then he returns to Rome and screens a special film Alfredo saved for him over the years, providing a clever but organically sound ‘cinematic’ conclusion. The longer original Italian version presumably retained longer versions of many earlier scenes, and other moments and scenes that would have fleshed out the show. But this 2002 new version is a director’s recut that reshuffles some scenes and reinstates a plot line, complete with characters and actors not seen in either version released before.

The added material is great, emotionally wrenching content that amplifies the original, and in a way pays off the movie—it’s strange to discover a whole new dimension to a film one already admires. Without divulging what the big deal is, I can say that events both in the past and the present are revealed to have been much more complicated. The added material is all central to the main romance, and will be an eye-opener. It makes Cinema Paradiso a much deeper and more ironic love story. A major role in the added footage is played by Brigitte Fossey, who was famous as the child star of 1952’s unforgettable Forbidden Games by René Clément... the little blonde girl. Forty years later, she’s still beautiful. She’s an excellent choice for a film dedicated to our cinema heritage.

So Miramax dodges the axe this time, by not just fixing one of their butchered releases, but allowing its director to restore his original cut. It is long, there’s no denying. Not only is the pacing a bit lacking, but the final modern section seems to be starting a new movie, and there’s always resistance to that. At three hours, seeing how its destiny would be DVD anyway, Tornatore should have worked in an intermission. I saw it in two halves over two nights, a plan I recommend. Once again, Ennio Morricone provides a score worth dying for... when is this man going to get his due at the Oscars?

Miramax’s DVD of Cinema Paradiso barely explains what it is. The extended long cut and the old release reside on opposite sides of a flipper disc, and both are handsomely mastered, although the new cut looks better and has a new Stereo mix.