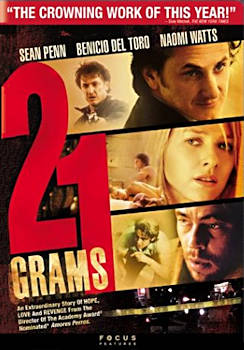

21 GRAMS

Released: 2003

Directed By: Alejandro González Iñárritu

Cast:

Sean Penn: Paul Rivers

Naomi Watts: Christina Peck

Benicio Del Toro: Jack Jordan

Melissa Leo: Marianne Jordan

Charlotte Gainsbourg: Mary Rivers

21 GRAMSReleased: 2003

|

|

Review by Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

Just when you thought Sean Penn had the Best Actor Oscar locked up for his career high in Mystic River, along comes tough competition: himself. In this scorcher of a drama from Mexican director Alejandro González Iñárritu—it’s only his second film, after the brilliant Amores Perros, and his first in English—Penn burns with ferocity and feeling as Paul, a math professor faced with the possibility of death after a heart transplant. His wife (Charlotte Gainsbourg) wants to have a baby, something of him left behind. Paul sees spirituality in terms of numbers, the twenty-one grams (the weight of a hummingbird, a chocolate bar or a stack of five nickels) that leave our bodies at death. Is it the weight of the soul?

Clearly, Iñárritu and screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga aren’t afraid of tackling big issues or splintering a plot—as they did in Amores Perros—to make audiences work at putting the pieces together. They intensify the puzzle by adding two equally damaged characters. Cristina (Naomi Watts), an ex-junkie, is the widow of the man whose heart Paul carries. Jack (Benicio Del Toro), the cause of the heart donor’s death, is an ex-con Jesus freak and alcoholic who loves and menaces his two kids and his wife (Melissa Leo, in a staggering portrayal of conflicted devotion). How these characters—all kicked hard by fate—unite in a brutal, erotic and achingly tender dance of death is for the film to tell you, not a review.

But know this: You won’t see more explosive acting this year. Penn’s continuing mastery of his craft amazes. Del Toro gets so far inside this ruined hulk that you flinch; he’s astonishing. And Watts is miraculous in an all-stops-out performance that bleeds with anger, guilt, sexual hunger and incalculable loss. That Iñárritu shapes something redemptive out of blasted lives is proof that he is a filmmaker of rare and startling grace.

Review by J. Hoberman, The Village Voice

Predicated on the magic of disjunctive editing, Alejandro González Iñárritu’s 21 Grams is as much jigsaw puzzle as movie. This fractured soap opera demands an active viewer. The soundtrack hiss at the New York Film Festival press screening was the whisper of people explaining it to each other.

No less showy than the young Mexican director’s 2000 debut, Amores Perros, but not nearly so brutal, 21 Grams (written by Guillermo Arriaga, who also scripted Amores Perros) opens somewhere in America with Paul (Sean Penn) and Cristina (Naomi Watts) alone together in bed; the movie spends much of the next two hours working its way back (or forward) to that scene. The first 30 minutes are a bewildering but not uninteresting succession of inexplicable situations involving spouses, children, hospitals, drugs, and the tormented ex-con former gangbanger turned Pentecostal, Jack (Benicio Del Toro).

Iñárritu’s tight camera focuses attention on the individuals rather than their context; his movie unfolds as a series of sharp vignettes, similar to Steven Soderbergh’s Traffic (also edited by Stephen Mirrione). Paul is seen awaiting a heart transplant, donating sperm, and suffering from a beating—not necessarily in that order. Cristina is shown haggardly coking up and cheerily packing her kids off to school. Paul’s angry wife (Charlotte Gainsbourg) wants to get pregnant by her dying husband. Jack languishes in jail and gets fired as a caddie because the country club swells object to his neck tattoo. Despite the unsorted jumble of temporal and causal relations, there is the sense that some fragile security is about to be destroyed. The mysteries deepen even after it becomes apparent that Cristina’s family has been obliterated by an accident that, as in Amores Perros, provides a mystical link between the three principals.

As Jack agonizes over his “duty to God” and Paul ponders his debt to his anonymous heart donor—the same premise employed by Clint Eastwood in Blood Work—Iñárritu ruminates upon the mystery of life. Accident or divine plan? Paul, a mathematician, flirtatiously tells Cristina that “there are so many things that have to happen for two people to meet.” (He doesn’t mention that he’s hired a private detective to facilitate their crossed paths.) The movie’s dubious philosophical treatise draws conviction from its high-powered cast—although no one could make convincing Penn’s final voice-over, explaining the title as the mass the body loses at death. Watts, who has the most difficult scenes, is splendidly mercurial; what’s surprising is that those professional storm clouds Penn and Del Toro are here as powerfully restrained as she is electrifying. (All three won acting awards when 21 Grams was shown in competition at the Venice Film Festival.)

The movie’s temporal logic is associative rather than structural—closer to chestnuts like Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad or the Julio Cortázar novel Hopscotch than the recent brainteasers Memento and Irreversible. Still, at once withholding and merciful, Iñárritu postpones the expected violence until the final act. A rush of tabloid nightmare images flashes by as a crucial motel-room brawl is shot with a brilliant absence of sound. You spend the movie dreading the sight of one thing, so of course you’re given another.

A straightforward 21 Grams would pack less emotional wallop. Indeed, given a linear progression, the movie’s New Age mysticism might seem merely sentimental. “How many lives do we live? How many times do we die?” It’s a measure of Iñárritu’s canniness as a cine-impresario that he understands that movies function as mass-produced recurrence and marketable eternity. 21 Grams is a sad puzzle, but then, so is life.

Review by Andrew O’Hehir, Salon.com

I haven’t quite made up my mind about 21 Grams. It has definitely stuck with me, like one of those troubling dreams that the first cup of coffee can’t clear from your head. It’s a brave and admirable film, but not an entirely successful one. Alejandro González Iñárritu’s first feature, the amazing Amores Perros, was an unrelenting blast of rock en español color and energy, a blood-drenched joyride through the streets of Mexico City that also possessed a startling, and heartbreaking, philosophical depth. In this new movie, González Iñárritu comes north of the border, and the results feel a lot dingier and a fair bit more pedantic.

His obsessions with death, with fate and with the almost senseless ability of the human animal to find hope in the grimmest of circumstances are intact, and so is the vertiginous, Buñuel-esque (or Tarantino-esque, or even Faulknerian) approach to time, which he sees as an endlessly elastic medium to be sliced, stretched and inverted at will. Like Amores Perros, this is a story about unrelated people from different class positions whose lives become inextricably linked by a cruel and seemingly random stroke of fate. Again, the incident is a terrible car accident that kills some people and skews the lives of others onto unpredictable trajectories.

González Iñárritu trusts his actors tremendously, and Sean Penn, Benicio Del Toro and Naomi Watts do some of their finest work as the haunted, increasingly haggard central trio who cannot shake free of each other. There are devastating moments here, moments of extraordinarily heightened perception that will convince you that this director has lost none of his dramatic power: Melissa Leo, who plays Del Toro’s wife, surveying the flashing lights and blanketed bodies of the accident scene with a horrified expression. (We don’t know the precise nature of her loss, although we soon will.) A mother who is forced to clean her dead daughters’ toys out of the garage one afternoon, entirely alone. When the fatal accident itself occurs (long after we know what has happened), we don’t actually see it: González Iñárritu shows us only a witness to the tragedy, a kid on the street using a leaf blower who stands there blankly and then drops his machine, still mindlessly leaf blowing, to run out of the frame.

But something about the combination of bleak moral fable, amped-up melodrama, disordered chronology and dirty-fingernail social realism never quite gels in 21 Grams. González Iñárritu doesn’t seem certain how to handle his norteamericano setting: Is this a portrait of specific people in a specific place, possibly intended as an indictment of the soulless anonymity of life in the United States? Or is this film set in that mythic American movieland customarily employed by Hollywood, that not quite New England, not quite California landscape (which is generally somewhere in Ontario)?

In fact, 21 Grams—the title refers not to cocaine, but to the amount of weight the human body purportedly loses at the moment of death—is set partly in Memphis and partly in New Mexico, but that never matters much. The locations may signify middle-class comfort, as with the luxurious house of Watts’ character (an architect’s wife), or the working-class fringe, as with the crowded bungalow where recovering alcoholic Benicio Del Toro lives with his wife and kids, or downscale decrepitude, as with the hot-sheet motel where Watts and Penn wind up late in the story with murder on their minds. But I think González Iñárritu is going for a mythic, almost generic quality: for the idea that this story could happen almost anywhere, to almost anybody.

That marks a significant departure from Amores Perros, which presented a highly specific cross-section of the Mexican capital, where class and geography so often determine destiny. The vibrant turquoises and blood crimsons and tropical greens of that film (so vividly sensual you could almost smell the tortillas frying in the back streets) are gone. 21 Grams looks dirty and almost incurably autumnal, as if cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto had dipped the raw footage in bourbon and then cured it with cigarette smoke. Which is appropriate enough; there’s so much smoking, drinking and drug use in this film, it should carry a warning from the surgeon general.

Make no mistake, González Iñárritu’s narrative method is fascinating, and if you get through the first 10 or 15 minutes OK, you’ll probably be hooked. He begins by giving us shards of information that seem to contradict each other: Here are Watts and Penn in that nowhere motel room, where they have clearly been lovers. Yet here is Watts at a 12-step meeting, talking gratefully about her husband and children, and there is Penn, critically ill with heart disease, sneaking a smoke in the john before his girlfriend (French actress Charlotte Gainsbourg) gets home. (For good measure, there’s Watts, doing up a bunch of coke in somebody’s bathroom. Before she got clean, or a relapse?)

Here also is Del Toro (playing a non-Latino character, entirely convincingly—maybe it took a Mexican director to try it) as an ex-con family man who has sworn off the bottle and now has “Jesus Saves!” painted on the back of his behemoth Dodge pickup. Yet here he is too, being issued a blanket and a uniform and being ushered into a prison cell—is this his past or his future? Even as we begin to grasp what nightmarish combination of these people (and that Dodge pickup) has interlocked all their lives, there are mysteries aplenty. How will all three of the principals wind up in that motel room? And why is one of them bleeding to death in the back seat of a car, while the other two desperately rush him to a hospital?

Part of González Iñárritu’s brilliance is his sense, captured by this narrative method, that lives happen to those who live them with a sort of simultaneity. Those of us who live long enough experience our younger and older selves, our triumphs and tragedies, even maybe our births and our deaths, as all happening in a bewildering, nonsequential welter. I’m also at least a little reluctant to criticize any movie that depicts the lives of middle-aged people with such tenderness and complexity. It isn’t just the young and the beautiful who torment themselves with what-ifs and might-have-beens, who face life-changing crises with an unstable mixture of stoicism and abject cowardice.

Watching Penn and Del Toro (and, to a lesser extent, the actually young and actually beautiful Watts) navigate the recesses of these damaged, ambivalent characters—worried, self-absorbed people who suspect they deserve the bad things that have happened to them and profoundly mistrust the good things—is pretty much worth the price of admission. But uprooted from their home soil, González Iñárritu and screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga can’t quite manage to make this gloomy, improbable stew of romance, film noir and pseudo-metaphysical speculation hang together. Foreign filmmakers have made many of the best movies about America, and I don’t doubt that the prodigiously talented González Iñárritu can follow suit. He might have to figure out what he actually thinks about our country first.