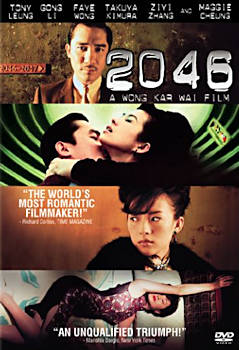

2046

Released: 2004

Directed By: Wong Kar Wai

Cast:

Tony Leung: Chow Mo Wan

Li Gong: Su Li Zhen (II)

Maggie Cheung: Su Li Zhen (1960)

Ziyi Zhang: Bai Ling

Faye Wong: Wang Jing Wen

2046Released: 2004

|

|

Review by Michael Atkinson, The Village Voice

HEARTBREAK HOTEL

In the Mood for Mood: Wong Kar Wai Finally Unveils His Symphonic Elegy to Lost Love

Coming at us along the suspenseful trajectory of a meteor we’ve helplessly watched approach for five years now, Wong Kar Wai’s 2046 is what you should’ve expected in your loneliest fanboy wet dreams: a sweaty, teeming, hot-to-the-touch life-swarm of a movie. From the portentous credits and first orchestral surge, the film knows it’s a post-millennial big bang, and thunderously demands your intimate surrender even as it refuses to let you get close. Wong has never sought to be graded for coloring inside the lines, and the movie’s present, “final” state is a living, not-finished-only-abandoned product of notorious production delays, reshoots, reconstructions, recastings, rewrites, firings, shutdowns (including for the 2003 SARS breakout), re-edits, and festival boondoggles. Reportedly, Wong began only with the number—the hotel room in In the Mood for Love—and an idea about a Thai hit man, or a Dickian futureworld of isolating technology. And the nagging ghost of heartbreak. If the contextual slippages are unavoidable, they’ve got nothing on the film itself, which careens, broods, glides, and tear-blooms around inside an untrustworthy and self-pitying memory, itself coming to resemble a movie vision that would not be tamed into completeness. One reason Wong’s film is so profoundly fascinating is that it feels as if it’s still evolving.

Can we get away with calling it poetic abstraction? 2046 retains fragments of virtually everything its creator had ever thought it might be, making it less a “project” than an organic coalescence of the artist as a not-so-young melancholic. In fact, in many ways it forms a Wong codex—his other films haunt the movie’s fringes and anterooms. Predominantly, In the Mood for Love serves as 2046’s agonizing prelude—after that, Tony Leung’s Mr. Chow lives out the remainder of the 1960s in an embittered state of romantic confusion, bouncing between cities and unfathomable women. He revisits the eponymous digs years later, and decides to board in the flat next door; still, the ubiquitous numeral also refers to the edge-moment when Deng Xiaoping said that Hong Kong would go “unchanged” after the 1997 Chinese takeover, a year represented in the film by Chow’s sci-fi stories of unattainable androids and wastrel romantics riding atomic tube-trains to nowhere. In Wong’s bruised narrative weft, 2046 is also a mysterious emotional destination, a frontier no one returns from, a rumor of a myth of love.

As with Wong’s contribution to the portmanteau film Eros (one of several detours taken during the making of this career-summarizing behemoth), humankind lives with, desires for, and listens to itself through thin urban walls, mottled-glass windows, and implacable doors. Newspaperman Chow skitters his narrated tale—as he writes it?—around, from Christmas to Christmas, 1966 to 1969, from Gong Li’s darkly vulnerable casino gambler to Ziyi Zhang’s tempestuous low-rent courtesan to Faye Wong’s emotionally unstable hotelier’s daughter, and back again, often in flashbacks and often in new encounters raw enough to rip the scabs right off. In Chow’s world, all women seem to have multiple identities, or stand as doubled-up avatars of his own lovelorn ideas, much of it sifting down to the earlier film’s intangible poignancy, and the new film’s spare and diffuse glimpses of Maggie Cheung, appearing and vanishing suddenly like a sense memory catching on as you pass and sending you lost into your own labyrinths.

2046 is all texture, a conquest of formal content over content-oppressed form, where the camera is in a perpetual state of inquiry, reframing the environment and its characters as a sort of methodological humility, and where visual and aural pathways boomerang down hallways, around corners, over rooftops. Mood is everything, trumped up by a score so rich with pop songs, bossa nova drama, and symphonic mournfulness it’s almost a movie on its own. 2046 may be a Chinese box of style geysers and earnest meta-irony, but that should not suggest there aren’t bleeding humans at the center of it: Gong, Zhang, and Wong (with her plate-sized eyes wandering astray) all deliver masterfully detailed portraits of women ensnared in romantic impossibility. Watch Zhang’s obstinate call girl barely register the debasement of being paid by the man she loves, and then jump painfully beyond it, and you’ll see a level of craft not trusted in this country. Leung, having endured the ordeal of the filmmaker’s titanic and fickle modus operandi, has well earned his iconic stature as a Bogartian everyman made world-weary by fate and his own selfishness. Still, one of my favorite characters is unseen, invoked only in a line of narration, a violent boyfriend described as being “like a bird that could never land.”

But 2046 bleeds mostly for itself; it’s a pulsing sign system of repeated melodramatic totems, ravishingly pregnant moments, and the sadness that comes from history and time’s arrow. But the trip is invigorating, bursting with the insistent vitality of first-time lovemaking. At first blush, the movie seems like one of those culminating über-works after which careers often fade to black—has Wong made the definitive Wongian film? Yes, but let’s stay, unlike Mr. Chow, in the present, where 2046 is just beginning to reveal itself.

Review by Richard Corliss, Time Magazine Asia Edition

IN THE MOOD FOR RAPTURE

After Years of Jokes That 2046 Wasn’t Going to be Finished Until 2046, It Has Opened—To Acclaim

Forget what you’ve heard about Hong Kong-based writer-director Wong Kar Wai: that he’s the tall dude in the cool shades who makes superhip movies the international art-house set loves for their languorous rhythms, their gorgeous-garish visual tones, their iconizing of alienation, their pioneering of a sultry cinematic language. Forget too the completion anxiety that attended his new film 2046—four years in the gestating, with scenes still being shot a few weeks ago, and which came so close to missing its slot in the Cannes Film Festival that, for the first time in memory, the screening times of three other official selections had to be changed at the last moment. And please try to ignore the melancholy fact that, though the Cannes jury gave four of its eight prizes to Asian directors and actors (including the Best Actress award to frequent Wong muse Maggie Cheung), none of them went to the festival’s finest film.

All this is true, but for the moment put it aside. What you need to know, what 2046 makes unavoidably clear, is that Wong Kar Wai is the most romantic filmmaker in the world. In incandescent images of glamorous performers, he details love’s anguish and rapture, which are often the same thing. Beautiful women throw themselves at handsome men—Leslie Cheung and Tony Leung—and the men often step aside. Love, the playwright Terry Johnson wrote, is something you fall in. Wong’s films make art out of that vertiginous feeling. They soar as their characters plummet.

2046 is a sequel of sorts to Wong’s In the Mood for Love, which premiered at Cannes in 2000 and enjoyed worldwide acclaim. That movie, set in Hong Kong in 1962, concerned the furtive affair of a married journalist, Chow Mo-wan (Leung), and a married woman (Maggie Cheung) who lives in the same boarding house. The new film follows Chow’s erotic adventures for the next decade or so, mainly with the alluring Bai Ling (Zhang Ziyi), and occasionally dips into the past, in reveries of Lulu the vamp (Carina Lau) and the tragic-masked Su Lizhen (Gong Li). Chow is now a writer of science-fiction novels. They take him and the audience into the year 2046, where he dallies with the android Wang Jing-wen (Faye Wong).

“He thought he wrote about the future,” the film’s narration says of Chow, “but it really was the past. In his novel, a mysterious train left for 2046 every once in a while. Everyone who went there had the same intention: to recapture their lost memories.” Chow Mo-wan, then, could be Wong Kar Wai, or indeed any other writer who becomes fascinated by his own creations; he plays with them, tries to discard them, is haunted by them as by lost memories. The movie goes further: it suggests that, once they are born in a writer’s imagination, these fictions, these women are alive. They can fall in love, which is wonderful for them to feel, and they can experience the pain of love, which is wonderful for us to see.

Wong’s films are a snap to decode for anyone familiar with the tropes of classic movie romance. Consider just three. Music: a slow samba can seduce two strangers into moving to each other’s emotional time, and 2046 sways to Perfidia and Quizás, Quizás, Quizás. Cigarettes: everyone puffs away pensively; the fumes wrap the characters in a retro-chic warmth as they dedicate themselves to that mesmeric movie rite, the sacrament of smoking. The kiss: 2046 has one of the great ones, between Chow and Su. He stands her against a wall and presses mouth to mouth. He moves back, and we see Su’s lipstick violently smeared. A tear courses down her right cheek, then another down her left. It is a kiss like an assault; it has crushed not just her lips but her heart.

The camera, John Berger once famously said, is a man looking at a woman. Movie romance is certainly a snapshot of a beautiful woman suffering. The main function of Chow—played by Leung as a sensitive gigolo whose smirk can mature into a sigh—is to direct our glance to all the fabulous women in the cast. The camera, mainly manned by Christopher Doyle, prowls around the women like a lover in the first flush of passion. It captures and caresses the actresses’ radiance: Lau’s bold sensuality, Faye Wong’s elfin resiliency, Gong Li’s fragile hauteur. Zhang, in a panoply of pouts, flirtations and surrendering smiles, is at her most ravishing and nuanced, especially when swathed in the spectacular cheongsams of costume designer (and editor and production designer) William Chang.

This year is still relatively young, and Wong’s romantic epic, in the version shown at Cannes, is not quite finished. Still, we say that—because of its passion, its craft, its belief in the grace and pain of love—2046 is the film of 2004.