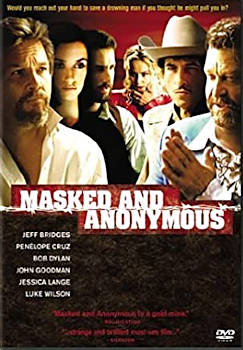

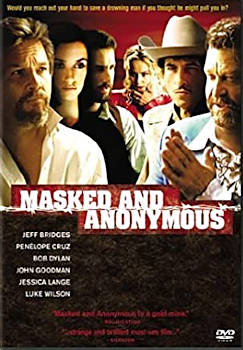

MASKED AND ANONYMOUS

Released: 2003

Directed by: Larry Charles

Written by: Bob Dylan & Larry Charles

Cast:

Bob Dylan: Jack Fate

Jeff Bridges: Tom Friend

John Goodman: Uncle Sweetheart

Jessica Lange: Nina Veronica

Penélope Cruz: Pagan Lace

Luke Wilson: Bobby Cupid

Angela Bassett: Mistress

Bruce Dern: Editor

Ed Harris: Oscar Vogel

Val Kilmer: Animal Wrangler

|

|

Review by Ron Rosenbaum, The New York Observer

BOB DYLAN UNDONE

Surrounded by Mythologizers, Bobby D. Makes Whacky Movie—His Masked and Anonymous Is a Wheezy Vanity Production Concocted by Ga-Ga Suck-Ups and Hollywood Bobolators

“Be kind, be really kind,” a prominent literary figure (and Dylan fan) admonished me, just before a screening of Masked and Anonymous, Dylan’s new film. I think he knew what was coming. And I tried, I’ve really tried to be kind. After all, the stakes are considerable: the return to film of one of the great American visionary artists. But sometimes, as the Nick Lowe song goes, “You got to be cruel to be kind.” And, in this case, the kindest thing I can say is this: Bob Dylan needs a friend. It’s painful (and a little cruel) to say, but that was my chief reaction to having seen Masked and Anonymous, not once, but twice.

Yes, I’m sure he has plenty of “friends”—all the people who told him his new movie was brilliant in concept and execution: “don’t change a thing, Bob.” All the professors and poets who shamelessly sucked up to him with their praise. I’m sure they were really good friends. (And I’m sure there are some hardcore fans who will find the film fabulous.) Maybe what I’m saying is that he needs a different kind of friend, the kind who could say to him, for instance: Don’t you realize how incredibly vain your pose of humility in this film makes you seem? Don’t you realize how silly it is to call your character “Jack Fate”? Don’t you realize that you’ve made several lifetimes’ worth of brilliant music? (Only a couple of instances of which are on the soundtrack.) You don’t need to make a painfully pretentious film that does nothing but diminish the respect the music deserves.

I have a feeling I’m going to burn a lot of bridges by saying this. And it hurts to say it; it hurts to be critical of someone whose work has earned my admiration and gratitude over a lifetime. But really, this film made me angry. Not so much at Bob Dylan, but at the yes-men and enablers who let him appear like this.

Or am I being unfair to his associates? Am I trying to shield Dylan himself from responsibility? After all, for someone who famously doesn’t suffer fools gladly, he certainly suffers flatterers. Is the sensibility behind this film’s cheap, antiquated surrealism, clichéd allegory, labored aphorisms and overblown portentousness the same sensibility that created all those songs that sent up sententiousness? I hope not; I think not. (Although the word is that Dylan and his director, Larry Charles, were behind the supposedly pseudonymous duo credited with the screenplay.) I think that what happened is that he and his enablers made the terrible mistake of trying to literalize all the lovely allusiveness of the songs. Fixing it on film—like fixing it in concrete—in a way that makes it seem painfully obvious and clumsily cloddish. The difference between Dylan’s music and this film is the difference between art and a schlocky Bizzaro-world simulacrum of art.

I guess you can’t blame the Hollywood director and Hollywood stars who helped him realize it, because Masked and Anonymous bears Dylan’s imprimatur; it’s his vision. I just wish he had a friend to offer an alternative reaction to the Hollywood enablers, something on the order of, “Bob, this screenplay sucks.” Or at least, “Bob, please, not Jack Fate.”

Instead, he had former Seinfeld writer-producer Larry Charles (not Seinfeld co-creator Larry David), who directed Masked and whose worshipful comments on the film—and on Dylan—are (inadvertently) funnier than anything on Seinfeld. Mr. Charles told a pre-screening press conference at Sundance, where the film was first shown, that “I’ve been to the mountain, and I came back with the tablets. I’ve talked to the burning bush.” So let’s see: If Larry Charles is Moses, that makes Bob Dylan God. And then there’s the online review that calls Dylan “the Shakespeare of the Movies.” And then there’s the film itself, in which Dylan’s character repeatedly compares himself or is compared to Jesus, with references to “walking on water” and plays upon “coming back,” as if his filmic appearance were a Second Coming. Guys, get your story straight: Is he God or Jesus? And why leave out the Holy Ghost?

Once, in an essay about Dylan’s born-again period (reprinted in The Dylan Companion), I wrote: “Perhaps we’re lucky [Dylan’s] only claimed he’s found Jesus; it wouldn’t be totally surprising if he claimed he was Jesus.” The movie, unfortunately, does nothing to discourage this speculation.

He plays a guitar-strummin’ loner, Jack Fate, a really, really humble guy (you can tell by his really, really humble down-home suit and the air of superiority he affects toward everyone else—a sure sign of humility). He’s an aging singer-songwriter whose great, if unspecified, message has been forgotten by a sinful, Babylon-like world. He’s a Prodigal Son who’s been thrown into jail and then called back to “give a benefit.” On the way, he wanders “in my Father’s world,” gathering disciples (including one called, unfortunately, “Bobby Cupid” and a Judas called—get this—“Tom Friend”), radiating high-wattage humility and authenticity among all the phonies and con men, helping us to learn Important Truths (the media are deceitful! The music business is exploitative! America is, like, really materialistic, dude!)—revelations no one would have thought of otherwise. In the end he suffers punishment for another’s sins. I hate to say this, Bob, but if you had a real friend, he’d tell you: Anyone who flaunts his humility so flagrantly—makes a big movie mainly about his own humility, makes a spectacle of his humility—is, well, not necessarily truly humble. Even Jesus didn’t write his own Gospels. In his strenuous effort to appear self-effacing, he becomes self-defacing.

As I said, all of this is painful to write for someone who considers himself one of the world’s most intense fans of Bob Dylan’s music. Someone who thinks Dylan deserves to be admired as a person, as well, for a genuine authenticity and humility: He loves to play music for people and continues to tour small and medium venues relentlessly when he could easily rest on his laurels by now.

More pertinently—or perversely—I’m someone who’s even liked his previous two self-made movies (two if you consider the fragmentary collage known as Eat the Document a movie—and I do, even if it was patched together from outtakes of Don’t Look Back). I once served as a panelist on a Museum of Television and Radio symposium on Eat the Document’s mysteries, because I thought it had the joyously anarchic, creative and experimental spirit of his music, as opposed to the leaden, antiquated, programmatic “experimentalism” of Masked and Anonymous.

And I actually loved all four-plus hours of Dylan’s 1978 self-made film, Renaldo and Clara. Aside from the fact that the music was incomparable—mostly taken from the Rolling Thunder Revue, one of the great peaks of live Dylan—the film playfully explored the various and eccentric array of characters who embodied the Village folk scene, the bohemian musical culture from which he emerged. And there were people in the film who were permitted to display a sense of humor and irreverence, even toward Dylan himself—something painfully absent from Masked and Anonymous.

Do I need to mention my other Dylan-cred touchstones to justify being critical of M&A? Most Dylanophiles are familiar with some quotes from my 1978 Playboy interview, in which Dylan delineated, in a lovely way, the Sound—he described it to me as “that thin, that wild mercury sound”—he’d always sought in his music (see my reflections on “that wild mercury sound” in my May 28, 2001, Observer column). There’s even a Dylan bootleg entitled Thin Wild Mercury Music. And the official Dylan Web site (www.bobdylan.com) recently asked if they could post some of my previous Observer columns on Dylan, particularly on the mysterious lost “red notebook” that supposedly contained alternate lyrics for Blood on the Tracks. After this column, I’m not sure that will happen. But as my friend Jonathan Schwartz—an intense and perceptive Dylan fan who was once exiled from the ambit of his other musical hero, Frank Sinatra—suggested, my responsibility should not be to the star, but to my readers.

Still, I want to make clear that I was predisposed to like Masked and Anonymous, no matter how experimental and unconventional it might be. (The depressing thing about it was how soddenly conventional it was.) I’m not an obsessive fan. I don’t even own a single bootleg. But you couldn’t find anyone more receptive and sympathetic to the work of this artist. Except, perhaps, the legendary French girl in Soho—and maybe that’s part of the problem: that Dylan is surrounded by people who are so indiscriminate in their worship they might as well be the legendary French girl in Soho.

I’ve written about the legendary French girl in Soho before. She was the lovely and intense Dylan fan who forever defined the gold standard of Dylan devotion when Renaldo and Clara was released in 1978, and she proceeded to see the four-hour-plus film 26—26!—times in a row. Every showing of its brief run, she boasted. Now, as I said, I liked Renaldo and Clara. I was never bored the three times I saw it (twice while interviewing Dylan in L.A.). And I’ll grant that the music may never be surpassed. But the film itself is just not that good. Not 26-times-in-a-row good. But just about everybody involved in this new film sounds like they’re channeling the legendary French girl in Soho.

Listen, for instance, to the distinguished Princeton professor of history who was enlisted to write an introductory essay for the production notes handed out at one screening: “Masked and Anonymous is a manic film about the death agonies of one America and a chilling prophecy about the birth of a new one.” Heavy, dude!

Sadly for me, someone who is a huge fan of Dylan’s masterpiece, “Desolation Row,” the good professor compares this clumsy, heavy-handed, symbol-and-allegory-glutted film to that sublimely beautiful, mournful—and funny—song. The professor has not only taken the Kool-Aid, he’s mixed up a big pitcher for Bob as well. The essay captures in its condescension everything that is wrong with the Iron Curtain of sycophancy that surrounds Dylan. We are lectured sternly by the professor: “The film is layered...you won’t get all of it the first time around.” Later, and even more condescendingly, he reassures us that “no one should be intimidated” by all the very deep and profound stuff we will encounter. He wasn’t! He could handle it! And just in case we miss its potentially intimidating profundity, we’re told that we should think of it in terms of Melville and Moby-Dick: “Jack Fate has some of Ishmael’s detached, fish-eyed, all-observant qualities. The plot...describes a doomed America that is not exactly any America we know, but one that, like the Pequod, seems about to be splintered and swallowed up in a vortex.”

As Dylan famously observed of such exegetes:

You’re very well read, it’s well known

But something is happening here

And you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mr. Jones?

Now listen to the words of the poet laureate of England, Andrew Motion, as he weighs in on Masked and Anonymous. On the movie’s official Web site (www.sonyclassics.com/masked), Mr. Motion opines that the film asks the questions: “What value does art have in a corrupt world, and what use? How can the artist protect his gift from his admirers, let alone his detractors? And then there’s a...more personal level of interrogation [props for using the lit-crit buzz word ‘interrogation’!]: Can happiness be pursued, or must we wait for it to come to us? Are dreams an acceptable alternative to realities? Does that cloud look like a camel to you?” (I made up the last question).

The most relevant of these “interrogations” is “How can the artist protect his gift from his admirers”—admirers like the poet laureate, for instance. As the brilliant man of letters Frank Kermode (also in The Dylan Companion!) put it in Shakespeare’s Language, it’s important to be able to admit that, at times, Shakespeare wrote badly—or at least less well—if one wants to preserve some credibility for one’s exalted admiration of his best work. Otherwise, one falls into the trap of indiscriminate Bardolatry. So many Dylan aficionados are guilty of what might be called Bobolatry. (One of the few academics who avoids it is Christopher Ricks, which is why I look forward to his forthcoming book, Dylan’s Visions of Sin.)

The problem is that Dylan himself seems to have been taken in by the professors, who flatter him that he’s Melville when he’s something else, something sui generis, something that can’t fit into the familiar categories of Princeton professors (anyone remember “Day of the Locusts”?) and British laureates, something that shouldn’t be translated into lit-crit bullshit.

Still, when it comes to pretentiousness, it’s hard to surpass the insulting diminishment of Dylan that director Larry Charles inflicts upon us. Yes, I know that writing and producing episodes of Seinfeld and Mad About You undoubtedly qualifies him to issue pronouncements as if from Parnassus, but the simple-minded reductiveness, the Hollywood profundity of his quotes in the production notes are priceless: “The movie has three fundamental themes,” he tells us (I hope you’re taking notes). “First, it is Bob Dylan on the road not taken—what might the world be like without the transforming influence of our cultural icons?” (Indeed, much to ponder there: Like, where would the world be without Jerry Seinfeld?)

“Second,” Mr. Charles continues with his instructional lecture, “it is about the social masks and armors we all wear to remain hidden and protected from one another.” Yeah, dig it, dude: It’s like everyone’s so phony and uptight they can’t be real, except that guy Holden Caulfield and Bob Dylan and, of course, Larry Charles—so open, so vulnerable, so honest, so self-congratulatory.

“In this story,” Professor Charles continues, “each of the characters are brought to the brink and have no choice but to rip off the mask and reveal their true nature.” Yeah, rip off them masks, brothers and sisters. And you, Larry Charles—kick out the jams in your Seinfeld-funded mansion! The problem is with the “true nature” of the cardboard allegorical characters in Masked and Anonymous. Despite the heroic efforts of the poor star-fans (Jeff Bridges! Jessica Lange! John Goodman!), who emote furiously in a futile attempt to breathe life into dialogue whose obviousness is clumsily rubbed in our face—they have no mask to rip off. Indeed, they’re all mask—and, with the possible exception of the peerless Ms. Lange, there’s nothing underneath.

I wonder if Dylan realizes how bad his collaborators have made him look, how much his pose of humility in this film comes across as diva-like pretentiousness. Why not go all the way: Instead of Jack Fate, call your character Hank Humble or Jeremiah P. Gooddude? Somebody has to say it. I wish it weren’t me, but better it comes from someone who loves and admires his best work. Somebody has to say that on celluloid—on this piece of translucent celluloid, at least—the mask is just too transparent. The Emperor has no clothes—or rather a see-through wardrobe. Worse, the Emperor has no dignity. Every true fan of Bob Dylan should be indignant at his enablers, indignant on his behalf that no one around him would tell Dylan of the pretentious mediocrity this film clothes him in.

Oh well, I’m sure I’ll be a pariah in Bob-world after this. But for all I owe to him—the thrill, the pleasure, the exaltation to be found in his best work—I feel I owe him the truth he’s not getting from others. From those in thrall to Bobolatry. And besides, not all the news is bad. This September, they’re finally releasing a remastered version of Blood on the Tracks, Dylan at the absolute peak of his artistry. I plan to listen to it at least 26 times.